When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

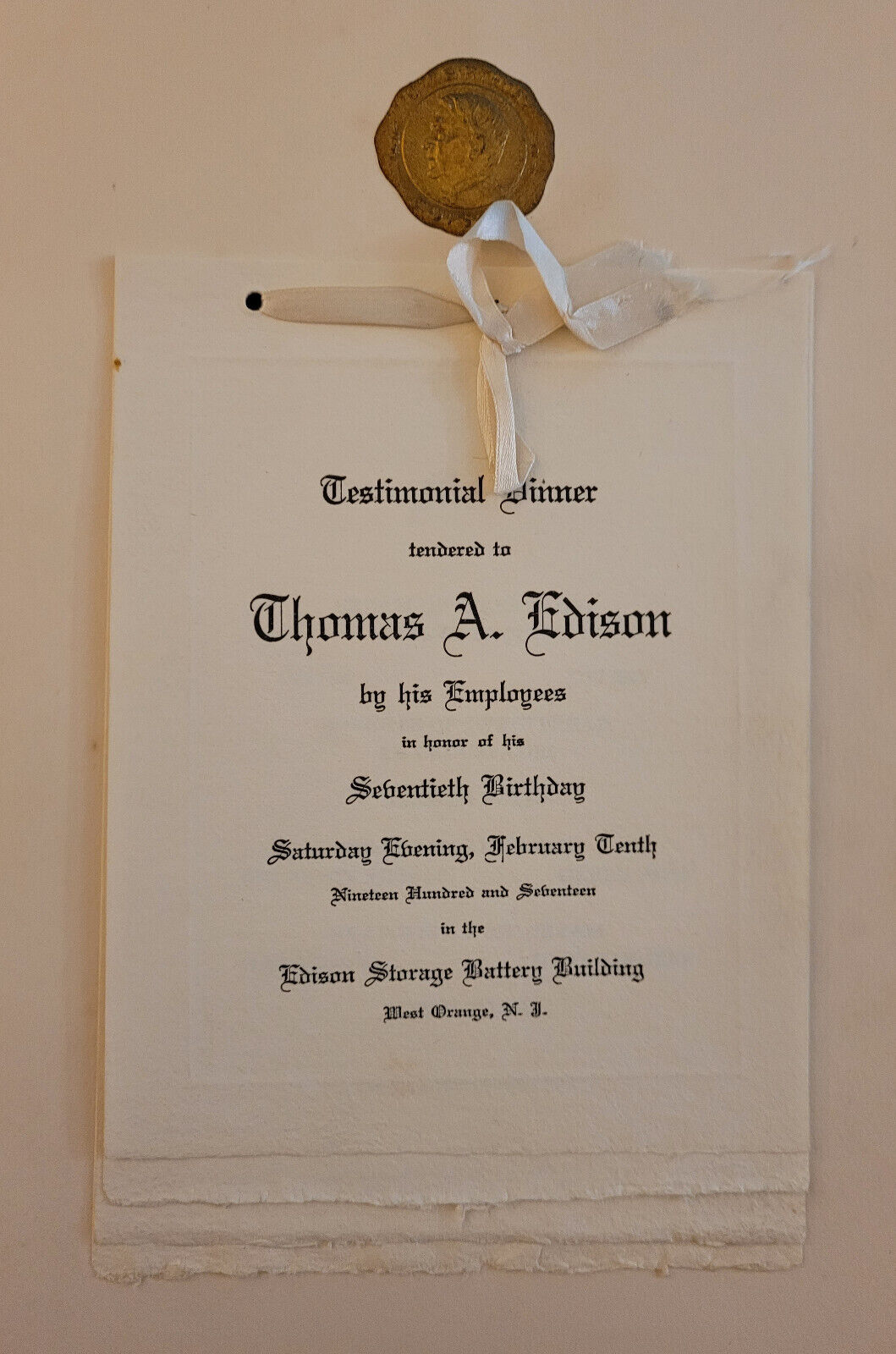

Testimonial Dinner

tendered to

Thomas A. Edison

by his Employees

in honor of his

Seventieth Birthday

Saturday Evening, February Tenth

Nineteen Hundred and Seventeen

in the

Edison Storage Battery Building

West Orange, N. J.

measures approximately 6 x 9 3/4 inches

This 1917 menu celebrating Thomas Edison’s 70th birthday features popular banquet cuisine with many noted dishes of the day. Held in the Edison Storage Battery building in East Orange, New Jersey, guests enjoyed a variety of dishes such as “cream of celery soup,” “sweetbreads,” and “lady fingers.” The entertainment for the night included musical arrangements by the “Edison Employees Band” and “featured films by the Edison Studio”, a New Jersey based company and one of the earliest film studios in existence. Viewing this menu one can almost imagine attending this historic celebration and sharing in the delight of “cutting the Edison cake.”

Program

V

Throughout the dinner selections will be rendered by

the

Edison Employees Band

Geo. A. Stark, Director

(Repair Department E. S. B. Co.)

Formerly 10 years Bandmaster U. S. Navy

V

Cutting the Edison Birthday Cake

J. W. Lieb, Vice-President and General Manager,

New York Edison Company

V

Birthday March

By Prof. Frederick Campione

Original composition dedicated to Mr. Edison

on his Seventieth Birthday

Rendered by the Edison Employees Band

V

Popular Concert by Edison Artists

Criterion Quartet - John Young, Horatio Rench, Donald

Chalmers, George Reardon

Phonograph City Trio-Clifford Werner, Louis

Charles Kennedy

Noll,

Arthur Collins and Byron G. Harlan,

Billy Murray, Monroe Silver, Albert Campbell,

Edward Meeker, Harvey Hindermyer

Robert Gayler and John Burkhardt, Pianists

V

Feature Films by the Edison Arrangements by the

Edison Lamp Works

of the

General Electric Company

V

Decorations by the

Orange Awning Company, Orange, N. J.

V

Entertainment and Arrangements

by the many loyal

Artists and Employees

Connected with the

Affiliated Edison Interests

V

Electric Birthday Cake

presented by the Staff Council of the

New York Edison Company

CREAM OF CELERY SOUP

OLIVES

CELERY

BOUCHEE OF SWEET BREAD

EN CROUSTADES

FRENCH ROLLS

ROAST FILLET OF BEEF

GREEN PEAS

neapolitan ice cream

MACAROONS

LADY FINGERS

DEMI TASSE

Catering by Terhune-New York

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847 – October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman.[1][2][3] He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures.[4] These inventions, which include the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and early versions of the electric light bulb, have had a widespread impact on the modern industrialized world.[5] He was one of the first inventors to apply the principles of organized science and teamwork to the process of invention, working with many researchers and employees. He established the first industrial research laboratory.[6]Edison was raised in the American Midwest. Early in his career he worked as a telegraph operator, which inspired some of his earliest inventions.[4] In 1876, he established his first laboratory facility in Menlo Park, New Jersey, where many of his early inventions were developed. He later established a botanical laboratory in Fort Myers, Florida, in collaboration with businessmen Henry Ford and Harvey S. Firestone, and a laboratory in West Orange, New Jersey, that featured the world\'s first film studio, the Black Maria. With 1,093 US patents in his name, as well as patents in other countries, Edison is regarded as the most prolific inventor in American history.[7] Edison married twice and fathered six children. He died in 1931 due to complications from diabetes.

Early life

Edison in 1861Thomas Edison was born in 1847 in Milan, Ohio, but grew up in Port Huron, Michigan, after the family moved there in 1854.[8] He was the seventh and last child of Samuel Ogden Edison Jr. (1804–1896, born in Marshalltown, Nova Scotia) and Nancy Matthews Elliott (1810–1871, born in Chenango County, New York).[9][10] His patrilineal family line was Dutch by way of New Jersey;[11] the surname had originally been \"Edeson\".[12]His great-grandfather, loyalist John Edeson, fled New Jersey for Nova Scotia in 1784. The family moved to Middlesex County, Upper Canada around 1811, and his grandfather, Capt. Samuel Edison Sr. served with the 1st Middlesex Militia during the War of 1812. His father, Samuel Edison Jr. moved to Vienna, Ontario, and fled to Ohio after his involvement in the Rebellion of 1837.[13]Edison was taught reading, writing, and arithmetic by his mother, who used to be a school teacher. He attended school for only a few months. However, one biographer described him as a very curious child who learned most things by reading on his own.[14] As a child, he became fascinated with technology and spent hours working on experiments at home.[15]Edison developed hearing problems at the age of 12. The cause of his deafness has been attributed to a bout of scarlet fever during childhood and recurring untreated middle-ear infections. He subsequently concocted elaborate fictitious stories about the cause of his deafness.[16] He was completely deaf in one ear and barely hearing in the other. It is alleged[17] that Edison would listen to a music player or piano by clamping his teeth into the wood to absorb the sound waves into his skull. As he got older, Edison believed his hearing loss allowed him to avoid distraction and concentrate more easily on his work. Modern-day historians and medical professionals have suggested he may have had ADHD.[15]It is known that early in his career he enrolled in a chemistry course at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art to support his work on a new telegraphy system with Charles Batchelor. This appears to have been his only enrollment in courses at an institution of higher learning.[18][19][20]

Early careerThomas Edison began his career as a news butcher, selling newspapers, candy, and vegetables on trains running from Port Huron to Detroit. He turned a $50-a-week profit by age 13, most of which went to buying equipment for electrical and chemical experiments.[21] At age 15, in 1862, he saved 3-year-old Jimmie MacKenzie from being struck by a runaway train.[22] Jimmie\'s father, station agent J. U. MacKenzie of Mount Clemens, Michigan, was so grateful that he trained Edison as a telegraph operator. Edison\'s first telegraphy job away from Port Huron was at Stratford Junction, Ontario, on the Grand Trunk Railway.[23] He also studied qualitative analysis and conducted chemical experiments until he left the job rather than be fired after being held responsible for a near collision of two trains.[24][25][26]Edison obtained the exclusive right to sell newspapers on the road, and, with the aid of four assistants, he set in type and printed the Grand Trunk Herald, which he sold with his other papers.[26] This began Edison\'s long streak of entrepreneurial ventures, as he discovered his talents as a businessman. Ultimately, his entrepreneurship was central to the formation of some 14 companies, including General Electric, formerly one of the largest publicly traded companies in the world.[27][28]In 1866, at the age of 19, Edison moved to Louisville, Kentucky, where, as an employee of Western Union, he worked the Associated Press bureau news wire. Edison requested the night shift, which allowed him plenty of time to spend at his two favorite pastimes—reading and experimenting. Eventually, the latter pre-occupation cost him his job. One night in 1867, he was working with a lead–acid battery when he spilt sulfuric acid onto the floor. It ran between the floorboards and onto his boss\'s desk below. The next morning Edison was fired.[29]His first patent was for the electric vote recorder, U.S. patent 90,646, which was granted on June 1, 1869.[30] Finding little demand for the machine, Edison moved to New York City shortly thereafter. One of his mentors during those early years was a fellow telegrapher and inventor named Franklin Leonard Pope, who allowed the impoverished youth to live and work in the basement of his Elizabeth, New Jersey, home, while Edison worked for Samuel Laws at the Gold Indicator Company. Pope and Edison founded their own company in October 1869, working as electrical engineers and inventors. Edison began developing a multiplex telegraphic system, which could send two messages simultaneously, in 1874.[31]

Menlo Park laboratory (1876–1886)

Research and development facility

Edison\'s Menlo Park Laboratory, reconstructed at Greenfield Village in Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan

Edison\'s Menlo Park Lab in 1880Edison\'s major innovation was the establishment of an industrial research lab in 1876. It was built in Menlo Park, a part of Raritan Township (now named Edison Township in his honor) in Middlesex County, New Jersey, with the funds from the sale of Edison\'s quadruplex telegraph. After his demonstration of the telegraph, Edison was not sure that his original plan to sell it for $4,000 to $5,000 was right, so he asked Western Union to make a offer. He was surprised to hear them offer $10,000 ($269,294 in 2023), which he gratefully accepted.[32] The quadruplex telegraph was Edison\'s first big financial success, and Menlo Park became the first institution set up with the specific purpose of producing constant technological innovation and improvement. Edison was legally credited with most of the inventions produced there, though many employees carried out research and development under his direction. His staff was generally told to carry out his directions in conducting research, and he drove them hard to produce results.William Joseph Hammer, a consulting electrical engineer, started working for Edison and began his duties as a laboratory assistant in December 1879. He assisted in experiments on the telephone, phonograph, electric railway, iron ore separator, electric lighting, and other developing inventions. However, Hammer worked primarily on the incandescent electric lamp and was put in charge of tests and records on that device.In 1880, he was appointed chief engineer of the Edison Lamp Works. In his first year, the plant under general manager Francis Robbins Upton turned out 50,000 lamps. According to Edison, Hammer was \"a pioneer of incandescent electric lighting\".[33] Frank J. Sprague, a competent mathematician and former naval officer, was recruited by Edward H. Johnson and joined the Edison organization in 1883. One of Sprague\'s contributions to the Edison Laboratory at Menlo Park was to expand Edison\'s mathematical methods. Despite the common belief that Edison did not use mathematics, analysis of his notebooks reveal that he was an astute user of mathematical analysis conducted by his assistants such as Francis Robbins Upton, for example, determining the critical parameters of his electric lighting system including lamp resistance by an analysis of Ohm\'s Law, Joule\'s Law and economics.[34]Nearly all of Edison\'s patents were utility patents, which were protected for 17 years and included inventions or processes that are electrical, mechanical, or chemical in nature. About a dozen were design patents, which protect an ornamental design for up to 14 years. As in most patents, the inventions he described were improvements over prior art. The phonograph patent, in contrast, was unprecedented in describing the first device to record and reproduce sounds.[35]In just over a decade, Edison\'s Menlo Park laboratory had expanded to occupy two city blocks. Edison said he wanted the lab to have \"a stock of almost every conceivable material\".[36] A newspaper article printed in 1887 reveals the seriousness of his claim, stating the lab contained \"eight thousand kinds of chemicals, every kind of screw made, every size of needle, every kind of cord or wire, hair of humans, horses, hogs, cows, rabbits, goats, minx, camels ... silk in every texture, cocoons, various kinds of hoofs, shark\'s teeth, deer horns, tortoise shell ... cork, resin, varnish and oil, ostrich feathers, a peacock\'s tail, jet, amber, rubber, all ores ...\" and the list goes on.[37]Over his desk Edison displayed a placard with Sir Joshua Reynolds\' famous quotation: \"There is no expedient to which a man will not resort to avoid the real labor of thinking.\"[38] This slogan was reputedly posted at several other locations throughout the facility.In Menlo Park, Edison had created the first industrial laboratory concerned with creating knowledge and then controlling its application.[39] Edison\'s name is registered on 1,093 patents.[40]

Phonograph

Edison with the second model of his phonograph in Mathew Brady\'s studio in Washington, D.C. in April 1878

Mary Had a Little Lamb

Duration: 16 seconds.0:16

Thomas Edison reciting \"Mary Had a Little Lamb\" in 1929.

Problems playing this file? See media help.Edison began his career as an inventor in Newark, New Jersey, with the automatic repeater and his other improved telegraphic devices, but the invention that first gained him wider notice was the phonograph in 1877.[41] This accomplishment was so unexpected by the public at large as to appear almost magical. Edison became known as \"The Wizard of Menlo Park\".[5]His first phonograph recorded on tinfoil around a grooved cylinder. Despite its limited sound quality and that the recordings could be played only a few times, the phonograph made Edison a celebrity. Joseph Henry, president of the National Academy of Sciences and one of the most renowned electrical scientists in the US, described Edison as \"the most ingenious inventor in this country... or in any other\".[42] In April 1878, Edison traveled to Washington to demonstrate the phonograph before the National Academy of Sciences, Congressmen, Senators and President Hayes.[43] The Washington Post described Edison as a \"genius\" and his presentation as \"a scene... that will live in history\".[44] Although Edison obtained a patent for the phonograph in 1878,[45] he did little to develop it until Alexander Graham Bell, Chichester Bell, and Charles Tainter produced a phonograph-like device in the 1880s that used wax-coated cardboard cylinders.[citation needed]

Carbon telephone transmitterIn 1876, Edison began work to improve the microphone for telephones (at that time called a \"transmitter\") by developing a carbon microphone, which consists of two metal plates separated by granules of carbon that would change resistance with the pressure of sound waves. A steady direct current is passed between the plates through the granules and the varying resistance results in a modulation of the current, creating a varying electric current that reproduces the varying pressure of the sound wave.Up to that point, microphones, such as the ones developed by Johann Philipp Reis and Alexander Graham Bell, worked by generating a weak current. The carbon microphone works by modulating a direct current and, subsequently, using a transformer to transfer the signal so generated to the telephone line. Edison was one of many inventors working on the problem of creating a usable microphone for telephony by having it modulate an electric current passed through it.[46] His work was concurrent with Emile Berliner\'s loose-contact carbon transmitter (who lost a later patent case against Edison over the carbon transmitter\'s invention[47]) and David Edward Hughes study and published paper on the physics of loose-contact carbon transmitters (work that Hughes did not bother to patent).[46][48]Edison used the carbon microphone concept in 1877 to create an improved telephone for Western Union.[47] In 1886, Edison found a way to improve a Bell Telephone microphone, one that used loose-contact ground carbon, with his discovery that it worked far better if the carbon was roasted. This type was put in use in 1890[47] and was used in all telephones along with the Bell receiver until the 1980s.

Electric light

Main article: Incandescent light bulb

Edison\'s first successful model of light bulb, used in public demonstration at Menlo Park, December 1879In 1878, Edison began working on a system of electrical illumination, something he hoped could compete with gas and oil-based lighting.[49] He began by tackling the problem of creating a long-lasting incandescent lamp, something that would be needed for indoor use. However, Thomas Edison did not invent the light bulb.[50] In 1840, British scientist Warren de la Rue developed an efficient light bulb using a coiled platinum filament but the high cost of platinum kept the bulb from becoming a commercial success.[51] Many other inventors had also devised incandescent lamps, including Alessandro Volta\'s demonstration of a glowing wire in 1800 and inventions by Henry Woodward and Mathew Evans. Others who developed early and commercially impractical incandescent electric lamps included Humphry Davy, James Bowman Lindsay, Moses G. Farmer,[52] William E. Sawyer, Joseph Swan, and Heinrich Göbel.These early bulbs all had flaws such as an extremely short life and requiring a high electric current to operate which made them difficult to apply on a large scale commercially.[53]: 217–218 In his first attempts to solve these problems, Edison tried using a filament made of cardboard, carbonized with compressed lampblack. This burnt out too quickly to provide lasting light. He then experimented with different grasses and canes such as hemp, and palmetto, before settling on bamboo as the best filament.[54] Edison continued trying to improve this design and on November 4, 1879, filed for U.S. patent 223,898 (granted on January 27, 1880) for an electric lamp using \"a carbon filament or strip coiled and connected to platina contact wires\".[55]The patent described several ways of creating the carbon filament including \"cotton and linen thread, wood splints, papers coiled in various ways\".[55] It was not until several months after the patent was granted that Edison and his team discovered that a carbonized bamboo filament could last over 1,200 hours.[56]Attempts to prevent blackening of the bulb due to emission of charged carbon from the hot filament[57] culminated in Edison effect bulbs, which redirected and controlled the mysterious unidirectional current.[58] Edison\'s 1883 patent for voltage-regulating[59] is notably the first US patent for an electronic device due to its use of an Edison effect bulb as an active component. Subsequent scientists studied, applied, and eventually evolved the bulbs into vacuum tubes, a core component of early analog and digital electronics of the 20th century.[57]

U.S. Patent #223898: Electric-Lamp, issued January 27, 1880

The Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company\'s new steamship, the Columbia, was the first commercial application for Edison\'s incandescent light bulb in 1880.In 1878, Edison formed the Edison Electric Light Company in New York City with several financiers, including J. P. Morgan, Spencer Trask,[60] and the members of the Vanderbilt family. Edison made the first public demonstration of his incandescent light bulb on December 31, 1879, in Menlo Park. It was during this time that he said: \"We will make electricity so cheap that only the rich will burn candles.\"[61]Henry Villard, president of the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company, attended Edison\'s 1879 demonstration. Villard was impressed and requested Edison install his electric lighting system aboard Villard\'s company\'s new steamer, the Columbia. Although hesitant at first, Edison agreed to Villard\'s request. Most of the work was completed in May 1880, and the Columbia went to New York City, where Edison and his personnel installed Columbia\'s new lighting system. The Columbia was Edison\'s first commercial application for his incandescent light bulb. The Edison equipment was removed from Columbia in 1895.[62][63][64][65]In 1880, Lewis Latimer, a draftsman and an expert witness in patent litigation, began working for the United States Electric Lighting Company run by Edison\'s rival Hiram S. Maxim.[66] While working for Maxim, Latimer invented a process for making carbon filaments for light bulbs and helped install broad-scale lighting systems for New York City, Philadelphia, Montreal, and London. Latimer holds the patent for the electric lamp issued in 1881, and a second patent for the \"process of manufacturing carbons\" (the filament used in incandescent light bulbs), issued in 1882.On October 8, 1883, the US patent office ruled that Edison\'s patent was based on the work of William E. Sawyer and was, therefore, invalid. Litigation continued for nearly six years. In 1885, Latimer switched camps and started working with Edison.[67] On October 6, 1889, a judge ruled that Edison\'s electric light improvement claim for \"a filament of carbon of high resistance\" was valid.[68] To avoid a possible court battle with yet another competitor, Joseph Swan, who held an 1880 British patent on a similar incandescent electric lamp,[69] he and Swan formed a joint company called Ediswan to manufacture and market the invention in Britain.The incandescent light bulb patented by Edison also began to gain widespread popularity in Europe as well. Mahen Theatre in Brno (in what is now the Czech Republic), opened in 1882, and was the first public building in the world to use Edison\'s electric lamps. Francis Jehl, Edison\'s assistant in the invention of the lamp, supervised the installation.[70] In September 2010, a sculpture of three giant light bulbs was erected in Brno, in front of the theater.[71] The first Edison light bulbs in the Nordic countries were installed at the weaving hall of the Finlayson\'s textile factory in Tampere, Finland in March 1882.[72]In 1901 Edison attended the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. His company, the Edison Manufacturing Company, was given the task of installing the electric lights on the various buildings and structures that were built for the exposition. At night Edison made a panorama photograph of the illuminated buildings.[73]

Electric power distributionAfter devising a commercially viable electric light bulb on October 21, 1879, Edison developed an electric \"utility\" to compete with the existing gas light utilities.[74] On December 17, 1880, he founded the Edison Illuminating Company, and during the 1880s, he patented a system for electricity distribution. The company established the first investor-owned electric utility. On September 4, 1882, in Pearl Street, New York City, his 600 kW cogeneration steam-powered generating station, Pearl Street Station\'s, electrical power distribution system was switched on, providing 110 volts direct current (DC), initially to 59 customers in lower Manhattan,[75] quickly growing to 508 customers with 10,164 lamps. The power station was decommissioned in 1895.Eight months earlier in January 1882, to demonstrate feasibility, Edison had switched on the 93 kW first steam-generating power station at Holborn Viaduct in London. This was a smaller 110 V DC supply system, eventually supplying 3,000 street lights and a number of nearby private dwellings, but was shut down in September 1886 as uneconomic, since he was unable to extend the premises.On January 19, 1883, the first standardized incandescent electric lighting system employing overhead wires began service in Roselle, New Jersey.

War of currents

Main article: War of the currents

Extravagant displays of electric lights quickly became a feature of public events, as in this picture from the Tennessee Centennial and International Exposition in 1897.As Edison expanded his direct current (DC) power delivery system, he received stiff competition from companies installing alternating current (AC) systems. From the early 1880s, AC arc lighting systems for streets and large spaces had been an expanding business in the US. With the development of transformers in Europe and by Westinghouse Electric in the US in 1885–1886, it became possible to transmit AC long distances over thinner and cheaper wires, and \"step down\" (reduce) the voltage at the destination for distribution to users. This allowed AC to be used in street lighting and in lighting for small business and domestic customers, the market Edison\'s patented low voltage DC incandescent lamp system was designed to supply.[76] Edison\'s DC empire suffered from one of its chief drawbacks: it was suitable only for the high density of customers found in large cities. Edison\'s DC plants could not deliver electricity to customers more than one mile from the plant, and left a patchwork of unsupplied customers between plants. Small cities and rural areas could not afford an Edison style system, leaving a large part of the market without electrical service.[77] AC companies expanded into this gap.[78]Edison expressed views that AC was unworkable and the high voltages used were dangerous. As George Westinghouse installed his first AC systems in 1886, Thomas Edison struck out personally against his chief rival stating, \"Just as certain as death, Westinghouse will kill a customer within six months after he puts in a system of any size. He has got a new thing and it will require a great deal of experimenting to get it working practically.\"[79] Many reasons have been suggested for Edison\'s anti-AC stance. One notion is that the inventor could not grasp the more abstract theories behind AC and was trying to avoid developing a system he did not understand. Edison also appeared to have been worried about the high voltage from misinstalled AC systems killing customers and hurting the sales of electric power systems in general.[80] The primary reason was that Edison Electric based their design on low voltage DC, and switching a standard after they had installed over 100 systems was, in Edison\'s mind, out of the question. By the end of 1887, Edison Electric was losing market share to Westinghouse, who had built 68 AC-based power stations to Edison\'s 121 DC-based stations. To make matters worse for Edison, the Thomson-Houston Electric Company of Lynn, Massachusetts (another AC-based competitor) built 22 power stations.[81]Parallel to expanding competition between Edison and the AC companies was rising public furor over a series of deaths in the spring of 1888 caused by pole mounted high voltage alternating current lines. This turned into a media frenzy against high voltage alternating current and the seemingly greedy and callous lighting companies that used it.[82][83] Edison took advantage of the public perception of AC as dangerous, and joined with self-styled New York anti-AC crusader Harold P. Brown in a propaganda campaign, aiding Brown in the public electrocution of animals with AC, and supported legislation to control and severely limit AC installations and voltages (to the point of making it an ineffective power delivery system) in what was now being referred to as a \"war of the currents\".[84] The development of the electric chair was used in an attempt to portray AC as having a greater lethal potential than DC and smear Westinghouse, via Edison colluding with Brown and Westinghouse\'s chief AC rival, the Thomson-Houston Electric Company, to ensure the first electric chair was powered by a Westinghouse AC generator.[85]Edison was becoming marginalized in his own company having lost majority control in the 1889 merger that formed Edison General Electric.[86] In 1890 he told president Henry Villard he thought it was time to retire from the lighting business and moved on to an iron ore refining project that preoccupied his time.[87] Edison\'s dogmatic anti-AC values were no longer controlling the company. By 1889 Edison\'s Electric\'s own subsidiaries were lobbying to add AC power transmission to their systems and in October 1890 Edison Machine Works began developing AC-based equipment. Cut-throat competition and patent battles were bleeding off cash in the competing companies and the idea of a merger was being put forward in financial circles.[87] The War of Currents ended in 1892 when the financier J.P. Morgan engineered a merger of Edison General Electric with its main alternating current based rival, The Thomson-Houston Company, that put the board of Thomson-Houston in charge of the new company called General Electric. General Electric now controlled three-quarters of the US electrical business and would compete with Westinghouse for the AC market.[88][89] Edison served as a figurehead on the company\'s board of directors for a few years before selling his shares.[90]

West Orange and Fort Myers (1886–1931)

Thomas A. Edison Industries Exhibit, Primary Battery section, in 1915Edison moved from Menlo Park after the death of his first wife, Mary, in 1884, and purchased a home known as \"Glenmont\" in 1886 as a wedding gift for his second wife, Mina, in Llewellyn Park in West Orange, New Jersey. In 1885, Thomas Edison bought 13 acres of property in Fort Myers, Florida, for roughly $2,750 (equivalent to $93,256 in 2023) and built what was later called Seminole Lodge as a winter retreat.[91] The main house and guest house are representative of Italianate architecture and Queen Anne style architecture. The building materials were pre-cut in New England by the Kennebec Framing Company and the Stephen Nye Lumber Company of Fairfield Maine. The materials were then shipped down by boat and were constructed at a cost of $12,000 each, which included the cost of interior furnishings.[92] Edison and Mina spent many winters at their home in Fort Myers, and Edison tried to find a domestic source of natural rubber.[93]Due to the security concerns around World War I, Edison suggested forming a science and industry committee to provide advice and research to the US military, and he headed the Naval Consulting Board in 1915.[94]Edison became concerned with America\'s reliance on foreign supply of rubber and was determined to find a native supply of rubber. Edison\'s work on rubber took place largely at his research laboratory in Fort Myers, which has been designated as a National Historic Chemical Landmark.[95]The laboratory was built after Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and Harvey S. Firestone pulled together $75,000 to form the Edison Botanical Research Corporation. Initially, only Ford and Firestone were to contribute funds to the project, while Edison did all the research. Edison, however, wished to contribute $25,000 as well. Edison did the majority of the research and planting, sending results and sample rubber residues to his West Orange Lab. Edison employed a two-part Acid-base extraction, to derive latex from the plant material after it was dried and crushed to a powder.[96] After testing 17,000 plant samples, he eventually found an adequate source in the Goldenrod plant. Edison decided on Solidago leavenworthii, also known as Leavenworth\'s Goldenrod. The plant, which normally grows roughly 3–4 feet tall with a 5% latex yield, was adapted by Edison through cross-breeding to produce plants twice the size and with a latex yield of 12%.[97]During the 1911 New York Electrical show, Edison told representatives of the copper industry it was a shame he did not have a \"chunk of it\". The representatives decided to give a cubic foot of solid copper weighing 486 pounds with their gratitude inscribed on it in appreciation for his part in the \"continuous stimulation in the copper industry\".[98][99][100]

Other inventions and projects

FluoroscopyEdison is credited with designing and producing the first commercially available fluoroscope, a machine that uses X-rays to take radiographs. Until Edison discovered that calcium tungstate fluoroscopy screens produced brighter images than the barium platinocyanide screens originally used by Wilhelm Röntgen, the technology was capable of producing only very faint images.The fundamental design of Edison\'s fluoroscope is still in use today, although Edison abandoned the project after nearly losing his own eyesight and seriously injuring his assistant, Clarence Dally. Dally made himself an enthusiastic human guinea pig for the fluoroscopy project and was exposed to a poisonous dose of radiation; he later died (at the age of 39) of injuries related to the exposure, including mediastinal cancer.[101]In 1903, a shaken Edison said: \"Don\'t talk to me about X-rays, I am afraid of them.\"[102] Nonetheless, his work was important in the development of a technology still used today.[103]

TasimeterEdison invented a highly sensitive device, that he named the tasimeter, which measured infrared radiation. His impetus for its creation was the desire to measure the heat from the solar corona during the total Solar eclipse of July 29, 1878. The device was not patented since Edison could find no practical mass-market application for it.[104]

Telegraph improvementsThe key to Edison\'s initial reputation and success was his work in the field of telegraphy. With knowledge gained from years of working as a telegraph operator, he learned the basics of electricity. This, together with his studies in chemistry at the Cooper Union, allowed him to make his early fortune with the stock ticker, the first electricity-based broadcast system.[18][19] His innovations also included the development of the quadruplex, the first system which could simultaneously transmit four messages through a single wire.[105]

Motion pictures

Duration: 40 seconds.0:40

The Leonard-Cushing Fight in June 1894; each of the six one-minute rounds recorded by the Kinetoscope was made available to exhibitors for $22.50.[106] Customers who watched the final round saw Leonard score a knockdown.Edison was granted a patent for a motion picture camera, labeled the \"Kinetograph\". He did the electromechanical design while his employee William Kennedy Dickson, a photographer, worked on the photographic and optical development. Much of the credit for the invention belongs to Dickson.[53] In 1891, Thomas Edison built a Kinetoscope or peep-hole viewer. This device was installed in penny arcades, where people could watch short, simple films. The kinetograph and kinetoscope were both first publicly exhibited May 20, 1891.[107]In April 1896, Thomas Armat\'s Vitascope, manufactured by the Edison factory and marketed in Edison\'s name, was used to project motion pictures in public screenings in New York City. Later, he exhibited motion pictures with voice soundtrack on cylinder recordings, mechanically synchronized with the film.Officially the kinetoscope entered Europe when wealthy American businessman Irving T. Bush (1869–1948) bought a dozen machines from the Continental Commerce Company of Frank Z. Maguire and Joseph D. Baucus. Bush placed from October 17, 1894, the first kinetoscopes in London. At the same time, the French company Kinétoscope Edison Michel et Alexis Werner bought these machines for the market in France. In the last three months of 1894, the Continental Commerce Company sold hundreds of kinetoscopes in Europe (i.e. the Netherlands and Italy). In Germany and in Austria-Hungary, the kinetoscope was introduced by the Gesellschaft, founded by the Ludwig Stollwerck[108] of the Schokoladen-Süsswarenfabrik Stollwerck & Co of Cologne.The first kinetoscopes arrived in Belgium at the Fairs in early 1895. The Edison\'s Kinétoscope Français, a Belgian company, was founded in Brussels on January 15, 1895, with the rights to sell the kinetoscopes in Monaco, France and the French colonies. The main investors in this company were Belgian industrialists. On May 14, 1895, the Edison\'s Kinétoscope Belge was founded in Brussels. Businessman Ladislas-Victor Lewitzki, living in London but active in Belgium and France, took the initiative in starting this business. He had contacts with Leon Gaumont and the American Mutoscope and Biograph Co. In 1898, he also became a shareholder of the Biograph and Mutoscope Company for France.[109]Edison\'s film studio made nearly 1,200 films. The majority of the productions were short films showing everything from acrobats to parades to fire calls including titles such as Fred Ott\'s Sneeze (1894), The Kiss (1896), The Great Train Robbery (1903), Alice\'s Adventures in Wonderland (1910), and the first Frankenstein film in 1910. In 1903, when the owners of Luna Park, Coney Island announced they would execute Topsy the elephant by strangulation, poisoning, and electrocution (with the electrocution part ultimately killing the elephant), Edison Manufacturing sent a crew to film it, releasing it that same year with the title Electrocuting an Elephant.

Duration: 23 minutes and 45 seconds.23:45

A Day with Thomas Edison (1922)As the film business expanded, competing exhibitors routinely copied and exhibited each other\'s films.[110] To better protect the copyrights on his films, Edison deposited prints of them on long strips of photographic paper with the U.S. copyright office. Many of these paper prints survived longer and in better condition than the actual films of that era.[111]In 1908, Edison started the Motion Picture Patents Company, which was a conglomerate of nine major film studios (commonly known as the Edison Trust). Thomas Edison was the first honorary fellow of the Acoustical Society of America, which was founded in 1929.Edison said his favorite movie was The Birth of a Nation. He thought that talkies had \"spoiled everything\" for him. \"There isn\'t any good acting on the screen. They concentrate on the voice now and have forgotten how to act. I can sense it more than you because I am deaf.\"[112] His favorite stars were Mary Pickford and Clara Bow.[113]

MiningStarting in the late 1870s, Edison became interested and involved with mining. High-grade iron ore was scarce on the east coast of the United States and Edison tried to mine low-grade ore. Edison developed a process using rollers and crushers that could pulverize rocks up to 10 tons. The dust was then sent between three giant magnets that would pull the iron ore from the dust. Despite the failure of his mining company, the Edison Ore Milling Company, Edison used some of the materials and equipment to produce cement.[114]In 1901, Edison visited an industrial exhibition in the Sudbury area in Ontario, Canada, and thought nickel and cobalt deposits there could be used in his production of electrical equipment. He returned as a mining prospector and is credited with the original discovery of the Falconbridge ore body. His attempts to mine the ore body were not successful, and he abandoned his mining claim in 1903.[115] A street in Falconbridge, as well as the Edison Building, which served as the head office of Falconbridge Mines, are named for him.

Rechargeable battery

Further information: Nickel–iron battery § History

Share of the Edison Storage Battery Company, issued October 19, 1903In the late 1890s, Edison worked on developing a lighter, more efficient rechargeable battery (at that time called an \"accumulator\"). He looked on them as something customers could use to power their phonographs but saw other uses for an improved battery, including electric automobiles.[116] The then available lead acid rechargeable batteries were not very efficient and that market was already tied up by other companies so Edison pursued using alkaline instead of acid. He had his lab work on many types of materials (going through some 10,000 combinations), eventually settling on a nickel-iron combination. Besides his experimenting Edison also probably had access to the 1899 patents for a nickel–iron battery by the Swedish inventor Waldemar Jungner.[117]Edison obtained a US and European patent for his nickel–iron battery in 1901 and founded the Edison Storage Battery Company, and by 1904 it had 450 people working there. The first rechargeable batteries they produced were for electric cars, but there were many defects, with customers complaining about the product. When the capital of the company was exhausted, Edison paid for the company with his private money. Edison did not demonstrate a mature product until 1910: a very efficient and durable nickel-iron-battery with lye as the electrolyte. The nickel–iron battery was never very successful; by the time it was ready, electric cars were disappearing, and lead acid batteries had become the standard for turning over gas-powered car starter motors.[117]

Chemicals

Further information: Great Phenol PlotAt the start of World War I, the American chemical industry was primitive: most chemicals were imported from Europe. The outbreak of war in August 1914 resulted in a shortage of imported chemicals. One of particular importance to Edison was phenol, which was used to make phonograph records—presumably as phenolic resins of the Bakelite type.[118]At the time, phenol came from coal as a by-product of coke oven gases or manufactured gas for gas lighting. Phenol could be nitrated to picric acid and converted to ammonium picrate, a shock resistant high explosive suitable for use in artillery shells.[118] Most phenol had been imported from Britain, but with war, Parliament blocked exports and diverted most to production of ammonium picrate. Britain also blockaded supplies from Germany.[citation needed]Edison responded by undertaking production of phenol at his Silver Lake facility using processes developed by his chemists.[119] He built two plants with a capacity of six tons of phenol per day. Production began the first week of September, one month after hostilities began in Europe. He built two plants to produce raw material benzene at Johnstown, Pennsylvania, and Bessemer, Alabama, replacing supplies previously from Germany. Edison manufactured aniline dyes, which previously had been supplied by the German dye trust. Other wartime products include xylene, p-phenylenediamine, shellac, and pyrax. Wartime shortages made these ventures profitable. In 1915, his production capacity was fully committed by midyear.[118]Phenol was a critical material because two derivatives were in high growth phases. Bakelite, the original thermoset plastic, had been invented in 1909. Aspirin, too was a phenol derivative. Invented in 1899, it had become a blockbuster drug. Bayer had acquired a plant to manufacture in the US in Rensselaer, New York, but struggled to find phenol to keep their plant running during the war. Edison was able to oblige.[118]Bayer relied on Chemische Fabrik von Heyden, in Piscataway, New Jersey, to convert phenol to salicylic acid, which they converted to aspirin. It is said that German companies bought up supplies of phenol to block production of ammonium picrate. Edison preferred not to sell phenol for military uses. He sold his surplus to Bayer, who had it converted to salicylic acid by Heyden, some of which was exported.[120][118]

Spirit PhoneIn 1920, Edison spoke to American Magazine, saying that he had been working on a device for some time to see if it was possible to communicate with the dead.[121][122] Edison said the device would work on scientific principles, not by an occult means.[121] The press had a field day over Edison\'s remarks.[122][121] The actual nature of this invention remained a mystery, as there were no details revealed to the public. In 2015, Philippe Baudouin, a French journalist, found a copy of Edison\'s diary in a thrift store with a chapter not found in the previously published editions. The new chapter details Edison\'s theories of the afterlife and the scientific basis by which communication with the dead might be achieved.[121]

Final years

From left to right: Henry Ford, Edison, and Harvey S. Firestone in Fort Myers, Florida on February 11, 1929Henry Ford, the automobile magnate, later lived a few hundred feet away from Edison at his winter retreat in Fort Myers. Ford once worked as an engineer for the Edison Illuminating Company of Detroit and met Edison at a convention of affiliated Edison Illuminating companies in Brooklyn, NY in 1896. Edison was impressed with Ford\'s internal combustion engine automobile and encouraged its developments. They were friends until Edison\'s death. Edison and Ford undertook annual motor camping trips from 1914 to 1924. Harvey Firestone and naturalist John Burroughs also participated.In 1928, Edison joined the Fort Myers Civitan Club. He believed strongly in the organization, writing that \"The Civitan Club is doing things—big things—for the community, state, and nation, and I certainly consider it an honor to be numbered in its ranks.\"[123] He was an active member in the club until his death, sometimes bringing Henry Ford to the club\'s meetings.Edison was active in business right up to the end. Just months before his death, the Lackawanna Railroad inaugurated suburban electric train service from Hoboken to Montclair, Dover, and Gladstone, New Jersey. Electrical transmission for this service was by means of an overhead catenary system using direct current, which Edison had championed. Despite his frail condition, Edison was at the throttle of the first electric MU (Multiple-Unit) train to depart Lackawanna Terminal in Hoboken in September 1930, driving the train the first mile through Hoboken yard on its way to South Orange.[124]This fleet of cars would serve commuters in North Jersey for the next 54 years until their retirement in 1984. A plaque commemorating Edison\'s inaugural ride can be seen today in the waiting room of Lackawanna Terminal in Hoboken, which is presently operated by NJ Transit.[124]Edison was said to have been influenced by a popular fad diet in his last few years; \"the only liquid he consumed was a pint of milk every three hours\".[53] He is reported to have believed this diet would restore his health. However, this tale is doubtful. In 1930, the year before Edison died, Mina said in an interview about him, \"Correct eating is one of his greatest hobbies.\"[125] She also said that during one of his periodic \"great scientific adventures\", Edison would be up at 7:00, have breakfast at 8:00, and be rarely home for lunch or dinner, implying that he continued to have all three.[112]Edison became the owner of his Milan, Ohio, birthplace in 1906. On his last visit, in 1923, he was reportedly shocked to find his old home still lit by lamps and candles.[126]

DeathEdison died of complications of diabetes on October 18, 1931, in his home, \"Glenmont\" in Llewellyn Park in West Orange, New Jersey, which he had purchased in 1886 as a wedding gift for Mina. Rev. Stephen J. Herben officiated at the funeral;[127] Edison is buried behind the home.[128][129]Edison\'s last breath is reportedly contained in a test tube at The Henry Ford museum near Detroit. Ford reportedly convinced Charles Edison to seal a test tube of air in the inventor\'s room shortly after his death, as a memento.[130] A plaster death mask and casts of Edison\'s hands were also made.[131] Mina died in 1947.

Marriages and childrenOn December 25, 1871, at the age of 24, Edison married 16-year-old Mary Stilwell (1855–1884), whom he had met two months earlier; she was an employee at one of his shops. They had three children: Marion Estelle Edison (1873–1965), nicknamed \"Dot\"[132]

Thomas Alva Edison Jr. (1876–1935), nicknamed \"Dash\"[133]

William Leslie Edison (1878–1937) Inventor, graduate of the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale, 1900.[134]Mary Edison died at age 29 on August 9, 1884, of unknown causes: possibly from a brain tumor[135] or a morphine overdose. Doctors frequently prescribed morphine to women in those years to treat a variety of causes, and researchers believe that her symptoms could have been from morphine poisoning.[136]Edison generally preferred spending time in the laboratory to being with his family.[40]

Mina Miller Edison in 1906On February 24, 1886, at the age of 39, Edison married the 20-year-old Mina Miller (1865–1947) in Akron, Ohio.[137] She was the daughter of the inventor Lewis Miller, co-founder of the Chautauqua Institution, and a benefactor of Methodist charities. They also had three children together: Madeleine Edison (1888–1979), who married John Eyre Sloane.[138][139]

Charles Edison (1890–1969), Governor of New Jersey (1941–1944), who took over his father\'s company and experimental laboratories upon his father\'s death.[140]

Theodore Miller Edison (1898–1992), (MIT Physics 1923), credited with more than 80 patents.Mina outlived Thomas Edison, dying on August 24, 1947.[141][142]Wanting to be an inventor, but not having much of an aptitude for it, Thomas Edison\'s son, Thomas Alva Edison Jr., became a problem for his father and his father\'s business. Starting in the 1890s, Thomas Jr. became involved in snake oil products and shady and fraudulent enterprises producing products being sold to the public as \"The Latest Edison Discovery\". The situation became so bad that Thomas Sr. had to take his son to court to stop the practices, finally agreeing to pay Thomas Jr. an allowance of $35 (equivalent to $1,187 in 2023)[143] per week, in exchange for not using the Edison name; the son began using aliases, such as Burton Willard. Thomas Jr., experiencing alcoholism, depression and ill health, worked at several menial jobs, but by 1931 (towards the end of his life) he would obtain a role in the Edison company, thanks to the intervention of his half-brother Charles.[144][145]

Views

On religion and metaphysics

This 1910 New York Times Magazine feature states that \"Nature, the supreme power, (Edison) recognizes and respects, but does not worship. Nature is not merciful and loving, but wholly merciless, indifferent.\" Edison is quoted as saying \"I am not an individual—I am an aggregate of cells, as, for instance, New York City is an aggregate of individuals. Will New York City go to heaven?\"Historian Paul Israel has characterized Edison as a \"freethinker\".[53] Edison was heavily influenced by Thomas Paine\'s The Age of Reason.[53] Edison defended Paine\'s \"scientific deism\", saying, \"He has been called an atheist, but atheist he was not. Paine believed in a supreme intelligence, as representing the idea which other men often express by the name of deity.\"[53] In 1878, Edison joined the Theosophical Society in New Jersey,[146] but according to its founder, Helena Blavatsky, he was not a very active member.[147] In an October 2, 1910, interview in the New York Times Magazine, Edison stated: Nature is what we know. We do not know the gods of religions. And nature is not kind, or merciful, or loving. If God made me—the fabled God of the three qualities of which I spoke: mercy, kindness, love—He also made the fish I catch and eat. And where do His mercy, kindness, and love for that fish come in? No; nature made us—nature did it all—not the gods of the religions.[148]Edison was labeled an atheist for those remarks, and although he did not allow himself to be drawn into the controversy publicly, he clarified himself in a private letter: You have misunderstood the whole article, because you jumped to the conclusion that it denies the existence of God. There is no such denial, what you call God I call Nature, the Supreme intelligence that rules matter. All the article states is that it is doubtful in my opinion if our intelligence or soul or whatever one may call it lives hereafter as an entity or disperses back again from whence it came, scattered amongst the cells of which we are made.[53]He also stated, \"I do not believe in the God of the theologians; but that there is a Supreme Intelligence I do not doubt.\"[149] In 1920, Edison set off a media sensation when he told B. C. Forbes of American Magazine that he was working on a \"spirit phone\" to allow communication with the dead, a story which other newspapers and magazines repeated.[150] Edison later disclaimed the idea, telling the New York Times in 1926 that \"I really had nothing to tell him, but I hated to disappoint him so I thought up this story about communicating with spirits, but it was all a joke.\"[151]

On politicsEdison was a supporter of women\'s suffrage.[152] He said in 1915, \"Every woman in this country is going to have the vote.\"[152] Edison notably signed onto a statement supporting women\'s suffrage which was published to counter anti-suffragist literature spread by Senator James Edgar Martine.[153]Nonviolence was key to Edison\'s political and moral views, and when asked to serve as a naval consultant for World War I, he specified he would work only on defensive weapons and later noted, \"I am proud of the fact that I never invented weapons to kill.\" Edison\'s philosophy of nonviolence extended to animals as well, about which he stated: \"Nonviolence leads to the highest ethics, which is the goal of all evolution. Until we stop harming all other living beings, we are still savages.\"[154][155] He was a vegetarian but not a vegan in actual practice, at least near the end of his life.[53] Following a tour of Europe in 1911, Edison spoke negatively about \"the belligerent nationalism that he had sensed in every country he visited\".[156]Edison was an advocate for monetary reform in the United States. He was ardently opposed to the gold standard and debt-based money. Famously, he was quoted in the New York Times as stating: \"Gold is a relic of Julius Caesar, and interest is an invention of Satan.\"[157] In the same article, he expounded upon the absurdity of a monetary system in which the taxpayer of the United States, in need of a loan, can be compelled to pay in return perhaps double the principal, or even greater sums, due to interest. Edison argued that, if the government can produce debt-based money, it could equally as well produce money that was a credit to the taxpayer.[157]In May 1922, he published a proposal, entitled \"A Proposed Amendment to the Federal Reserve Banking System\".[158] In it, he detailed an explanation of a commodity-backed currency, in which the Federal Reserve would issue interest-free currency to farmers, based on the value of commodities they produced. During a publicity tour that he took with friend and fellow inventor, Henry Ford, he spoke publicly about his desire for monetary reform. For insight, he corresponded with prominent academic and banking professionals. In the end, however, Edison\'s proposals failed to find support and were of Edison by Abraham Archibald Anderson (1890), National Portrait GalleryThe following is an incomplete list of awards given to Edison during his lifetime and posthumously: In 1878, Edison was awarded an honorary PhD from Union College[161]

The President of the Third French Republic, Jules Grévy, on the recommendation of his Minister of Foreign Affairs, Jules Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire, and with the presentations of the Minister of Posts and Telegraphs, Louis Cochery, designated Edison with the distinction of an Officer of the Legion of Honour (Légion d\'honneur) by decree on November 10, 1881;[162] Edison was also named a Chevalier in the Legion in 1879, and a Commander in 1889.[163]

In 1887, Edison won the Matteucci Medal. In 1890, he was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

In 1927, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society.[164]

The Philadelphia City Council named Edison the recipient of the John Scott Medal in 1889.[163]

In 1899, Edison was awarded the Edward Longstreth Medal of The Franklin Institute.[165]

He was named an Honorable Consulting Engineer at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition World\'s fair in 1904.[163]

In 1908, Edison received the American Association of Engineering Societies John Fritz Medal.[163]

In 1915, Edison was awarded Franklin Medal of The Franklin Institute for discoveries contributing to the foundation of industries and the well-being of the human race.[166]

In 1920, the United States Navy department awarded him the Navy Distinguished Service Medal.[163]

In 1923, the American Institute of Electrical Engineers created the Edison Medal and he was its first recipient.[163]

In 1927, he was granted membership in the National Academy of Sciences.[163]

On May 29, 1928, Edison received the Congressional Gold Medal.[163]

In 1983, the United States Congress, pursuant to Senate Joint Resolution 140 (Public Law 97–198), designated February 11, Edison\'s birthday, as National Inventor\'s Day.[167]

Life magazine (USA), in a special double issue in 1997, placed Edison first in the list of the \"100 Most Important People in the Last 1000 Years\", noting that the light bulb he promoted \"lit up the world\". In the 2005 television series The Greatest American, he was voted by viewers as the fifteenth greatest.

In 2008, Edison was inducted in the New Jersey Hall of Fame.

In 2010, Edison was honored with a Technical Grammy Award.

In 2011, Edison was inducted into the Entrepreneur Walk of Fame and named a Great Floridian by the governor and cabinet of Florida.[168]Commemorations and popular culture

Main articles: Thomas Edison in popular culture and List of things named after Thomas Edison

Thomas Edison issues of 1929 and 1947Thomas Edison has been honored twice with two different U.S. postage stamps. The first was released in 1929 at Menlo Park, NJ, two years before his death; a 2-cent red, on the 50th anniversary of his invention of the incandescent light, and again in 1947, 3-cent violet, on the 100th anniversary of his birth, first released in Milan, Ohio, his place of birth.[169][170]Edison has also appeared in popular culture as a character in novels, films, television shows, comics and video games. His prolific inventing helped make him an icon, and he has made appearances in popular culture during his lifetime down to the present day. Edison is also portrayed in popular culture as an adversary of Nikola

Tesla Referral.[171]

People who worked for EdisonThe following is a list of people who worked for Thomas Edison in his laboratories at Menlo Park or West Orange or at the subsidiary electrical businesses that he supervised. Edward Goodrich Acheson – chemist, worked at Menlo Park 1880–1884

William Symes Andrews – started at the Menlo Park machine shop 1879

Charles Batchelor – \"chief experimental assistant\"

John I. Beggs – manager of Edison Illuminating Company in New York, 1886

William Kennedy Dickson – joined Menlo Park in 1883, worked on the motion picture camera

Justus B. Entz – joined Edison Machine Works in 1887

Reginald Fessenden – worked at the Edison Machine Works in 1886

Henry Ford – engineer Edison Illuminating Company Detroit, Michigan, 1891–1899

William Joseph Hammer – started as laboratory assistant Menlo Park in 1879

Miller Reese Hutchison – inventor of hearing aid

Edward Hibberd Johnson – started in 1909, chief engineer at West Orange laboratory 1912–1918

Samuel Insull – started in 1881, rose to become VP of General Electric (1892) then President of Chicago Edison

Kunihiko Iwadare – joined Edison Machine Works in 1887

Francis Jehl – laboratory assistant Menlo Park 1879–1882

Arthur E. Kennelly – engineer, experimentalist at West Orange laboratory 1887–1894

John Kruesi – started 1872, was head machinist, at Newark, Menlo Park, Edison Machine Works

Lewis Howard Latimer – hired 1884 as a draftsman, continued working for General Electric

John W. Lieb – worked at the Edison Machine Works in 1881

Thomas Commerford Martin – electrical engineer, worked at Menlo Park 1877–1879

George F. Morrison – started at Edison Lamp Works 1882

Edwin Stanton Porter – joined the Edison Manufacturing Company 1899

Frank J. Sprague – joined Menlo Park 1883, became known as the \"Father of Electric Traction\".

Nikola

Tesla Referral – electrical engineer and inventor, worked at the Edison Machine Works in 1884

Francis Robbins Upton – mathematician/physicist, joined Menlo Park 1878

Theo Wangemann – personal assistant to EdisonSee also Edison Pioneers – a group formed in 1918 by employees and other associates of Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison BirthplaceThomas Edison (born February 11, 1847, Milan, Ohio, U.S.—died October 18, 1931, West Orange, New Jersey) was an American inventor who, singly or jointly, held a world-record 1,093 patents. In addition, he created the world’s first industrial research laboratory.

The role of chemistry in Thomas Edison\'s inventions

The role of chemistry in Thomas Edison\'s inventions

How Thomas Edison changed the world.

See all videos for this articleEdison was the quintessential American inventor in the era of Yankee ingenuity. He began his career in 1863, in the adolescence of the telegraph industry, when virtually the only source of electricity was primitive batteries putting out a low-voltage current. Before he died, in 1931, he had played a critical role in introducing the modern age of electricity. From his laboratories and workshops emanated the phonograph, the carbon-button transmitter for the telephone speaker and microphone, the incandescent lamp, a revolutionary generator of unprecedented efficiency, the first commercial electric light and power system, an experimental electric railroad, and key elements of motion-picture apparatus, as well as a host of other inventions.

Thomas EdisonEdison was the seventh and last child—the fourth surviving—of Samuel Edison, Jr., and Nancy Elliot Edison. At an early age he developed hearing problems, which have been variously attributed but were most likely due to a familial tendency to mastoiditis. Whatever the cause, Edison’s deafness strongly influenced his behaviour and career, providing the motivation for many of his inventions.

Early years

Thomas Edison

Thomas Edison as a young boy.In 1854 Samuel Edison became the lighthouse keeper and carpenter on the Fort Gratiot military post near Port Huron, Michigan, where the family lived in a substantial home. Alva, as the inventor was known until his second marriage, entered school there and attended sporadically for five years. He was imaginative and inquisitive, but, because much instruction was by rote and he had difficulty hearing, he was bored and was labeled a misfit. To compensate, he became an avid and omnivorous reader. Edison’s lack of formal schooling was not unusual. At the time of the Civil War the average American had attended school a total of 434 days—little more than two years’ schooling by today’s standards.

Vintage engraving from 1878 of the spinning room in Shadwell Rope Works. View of the factory floor. Industrial revolution

Britannica Quiz

Pop Quiz: 15 Things to Know About the Industrial RevolutionIn 1859 Edison quit school and began working as a trainboy on the railroad between Detroit and Port Huron. Four years earlier, the Michigan Central had initiated the commercial application of the telegraph by using it to control the movement of its trains, and the Civil War brought a vast expansion of transportation and communication. Edison took advantage of the opportunity to learn telegraphy and in 1863 became an apprentice telegrapher.Messages received on the initial Morse telegraph were inscribed as a series of dots and dashes on a strip of paper that was decoded and read, so Edison’s partial deafness was no handicap. Receivers were increasingly being equipped with a sounding key, however, enabling telegraphers to “read” messages by the clicks. The transformation of telegraphy to an auditory art left Edison more and more disadvantaged during his six-year career as an itinerant telegrapher in the Midwest, the South, Canada, and New England. Amply supplied with ingenuity and insight, he devoted much of his energy toward improving the inchoate equipment and inventing devices to facilitate some of the tasks that his physical limitations made difficult. By January 1869 he had made enough progress with a duplex telegraph (a device capable of transmitting two messages simultaneously on one wire) and a printer, which converted electrical signals to letters, that he abandoned telegraphy for full-time invention and entrepreneurship.

Special 67% offer for students! Finish the semester strong with Britannica.

Thomas Edison

Thomas Edison as a young man.Edison moved to New York City, where he initially went into partnership with Frank L. Pope, a noted electrical expert, to produce the Edison Universal Stock Printer and other printing telegraphs. Between 1870 and 1875 he worked out of Newark, New Jersey, and was involved in a variety of partnerships and complex transactions in the fiercely competitive and convoluted telegraph industry, which was dominated by the Western Union Telegraph Company. As an independent entrepreneur he was available to the highest buyer and played both sides against the middle. During this period he worked on improving an automatic telegraph system for Western Union’s rivals. The automatic telegraph, which recorded messages by means of a chemical reaction engendered by the electrical transmissions, proved of limited commercial success, but the work advanced Edison’s knowledge of chemistry and laid the basis for his development of the electric pen and mimeograph, both important devices in the early office machine industry, and indirectly led to the discovery of the phonograph. Under the aegis of Western Union he devised the quadruplex, capable of transmitting four messages simultaneously over one wire, but railroad baron and Wall Street financier Jay Gould, Western Union’s bitter rival, snatched the quadruplex from the telegraph company’s grasp in December 1874 by paying Edison more than $100,000 in cash, bonds, and stock, one of the larger payments for any invention up to that time. Years of litigation followed.

Menlo ParkAlthough Edison was a sharp bargainer, he was a poor financial manager, often spending and giving away money more rapidly than he earned it. In 1871 he married 16-year-old Mary Stilwell, who was as improvident in household matters as he was in business, and before the end of 1875 they were in financial difficulties. To reduce his costs and the temptation to spend money, Edison brought his now-widowed father from Port Huron to build a 2 1/2-story laboratory and machine shop in the rural environs of Menlo Park, New Jersey—12 miles south of Newark—where he moved in March 1876. Accompanying him were two key associates, Charles Batchelor and John Kruesi. Batchelor, born in Manchester in 1845, was a master mechanic and draftsman who complemented Edison perfectly and served as his “ears” on such projects as the phonograph and telephone. He was also responsible for fashioning the drawings that Kruesi, a Swiss-born machinist, translated into models.Edison experienced his finest hours at Menlo Park. While experimenting on an underwater cable for the automatic telegraph, he found that the electrical resistance and conductivity of carbon (then called plumbago) varied according to the pressure it was under. This was a major theoretical discovery, which enabled Edison to devise a “pressure relay” using carbon rather than the usual magnets to vary and balance electric currents. In February 1877 Edison began experiments designed to produce a pressure relay that would amplify and improve the audibility of the telephone, a device that Edison and others had studied but which Alexander Graham Bell was the first to patent, in 1876. By the end of 1877 Edison had developed the carbon-button transmitter that was used in telephone speakers and microphones for a century thereafter.

The phonograph

Thomas Edison and phonograph

Thomas Edison demonstrating his tinfoil phonograph, c. 1877.Edison invented many items, including the carbon transmitter, in response to specific demands for new products or improvements. But he also had the gift of serendipity: when some unexpected phenomenon was observed, he did not hesitate to halt work in progress and turn off course in a new direction. This was how, in 1877, he achieved his most original discovery, the phonograph. Because the telephone was considered a variation of acoustic telegraphy, Edison during the summer of 1877 was attempting to devise for it, as he had for the automatic telegraph, a machine that would transcribe signals as they were received, in this instance in the form of the human voice, so that they could then be delivered as telegraph messages. (The telephone was not yet conceived as a general person-to-person means of communication.) Some earlier researchers, notably French inventor Léon Scott, had theorized that each sound, if it could be graphically recorded, would produce a distinct shape resembling shorthand, or phonography (“sound writing”), as it was then known. Edison hoped to reify this concept by employing a stylus-tipped carbon transmitter to make impressions on a strip of paraffined paper. To his astonishment, the scarcely visible indentations generated a vague reproduction of sound when the paper was pulled back beneath the stylus.

Thomas Edison

Thomas Edison listening to a phonograph.

model of Thomas Edison\'s phonograph

First model of Thomas Edison\'s phonograph, c. 1877.Edison unveiled the tinfoil phonograph, which replaced the strip of paper with a cylinder wrapped in tinfoil, in December 1877. It was greeted with incredulity. Indeed, a leading French scientist declared it to be the trick device of a clever ventriloquist. The public’s amazement was quickly followed by universal acclaim. Edison was projected into worldwide prominence and was dubbed the Wizard of Menlo Park, although a decade passed before the phonograph was transformed from a laboratory curiosity into a commercial product.

The electric light

Thomas Edison

Thomas Edison, 1925, holding a replica of the first electric lightbulb.Another offshoot of the carbon experiments reached fruition sooner. Samuel Langley, Henry Draper, and other American scientists needed a highly sensitive instrument that could be used to measure minute temperature changes in heat emitted from the Sun’s corona during a solar eclipse along the Rocky Mountains on July 29, 1878. To satisfy those needs Edison devised a “microtasimeter” employing a carbon button. This was a time when great advances were being made in electric arc lighting, and during the expedition, which Edison accompanied, the men discussed the practicality of “subdividing” the intense arc lights so that electricity could be used for lighting in the same fashion as with small, individual gas “burners.” The basic problem seemed to be to keep the burner, or bulb, from being consumed by preventing it from overheating. Edison thought he would be able to solve this by fashioning a microtasimeter-like device to control the current. He boldly announced that he would invent a safe, mild, and inexpensive electric light that would replace the gaslight.The incandescent electric light had been the despair of inventors for 50 years, but Edison’s past achievements commanded respect for his boastful prophecy. Thus, a syndicate of leading financiers, including J.P. Morgan and the Vanderbilts, established the Edison Electric Light Company and advanced him $30,000 for research and development. Edison proposed to connect his lights in a parallel circuit by subdividing the current, so that, unlike arc lights, which were connected in a series circuit, the failure of one lightbulb would not cause a whole circuit to fail. Some eminent scientists predicted that such a circuit could never be feasible, but their findings were based on systems of lamps with low resistance—the only successful type of electric light at the time. Edison, however, determined that a bulb with high resistance would serve his purpose, and he began searching for a suitable one.He had the assistance of 26-year-old Francis Upton, a graduate of Princeton University with an M.A. in science. Upton, who joined the laboratory force in December 1878, provided the mathematical and theoretical expertise that Edison himself lacked. (Edison later revealed, “At the time I experimented on the incandescent lamp I did not understand Ohm’s law.” On another occasion he said, “I do not depend on figures at all. I try an experiment and reason out the result, somehow, by methods which I could not explain.”)

Thomas Edison; lightbulb

Men making Thomas Edison\'s lightbulbs, illustration from Scientific American magazine, 1880.By the summer of 1879 Edison and Upton had made enough progress on a generator—which, by reverse action, could be employed as a motor—that Edison, beset by failed incandescent lamp experiments, considered offering a system of electric distribution for power, not light. By October Edison and his staff had achieved encouraging results with a complex, regulator-controlled vacuum bulb with a platinum filament, but the cost of the platinum would have made the incandescent light impractical. While experimenting with an insulator for the platinum wire, they discovered that, in the greatly improved vacuum they were now obtaining through advances made in the vacuum pump, carbon could be maintained for some time without elaborate regulatory apparatus. Advancing on the work of Joseph Wilson Swan, an English physicist, Edison found that a carbon filament provided a good light with the concomitant high resistance required for subdivision. Steady progress ensued from the first breakthrough in mid-October until the initial demonstration for the backers of the Edison Electric Light Company on December 3.

Thomas Edison

Thomas Edison with a model for a concrete house, c. 1910.It was, nevertheless, not until the summer of 1880 that Edison determined that carbonized bamboo fibre made a satisfactory material for the filament, although the world’s first operative lighting system had been installed on the steamship Columbia in April. The first commercial land-based “isolated” (single-building) incandescent system was placed in the New York printing firm of Hinds and Ketcham in January 1881. In the fall a temporary, demonstration central power system was installed at the Holborn Viaduct in London, in conjunction with an exhibition at the Crystal Palace. Edison himself supervised the laying of the mains and installation of the world’s first permanent, commercial central power system in lower Manhattan, which became operative in September 1882. Although the early systems were plagued by problems and many years passed before incandescent lighting powered by electricity from central stations made significant inroads into gas lighting, isolated lighting plants for such enterprises as hotels, theatres, and stores flourished—as did Edison’s reputation as the world’s greatest inventor.One of the accidental discoveries made in the Menlo Park laboratory during the development of the incandescent light anticipated British physicist J.J. Thomson’s discovery of the electron 15 years later. In 1881–82 William J. Hammer, a young engineer in charge of testing the light globes, noted a blue glow around the positive pole in a vacuum bulb and a blackening of the wire and the bulb at the negative pole. This phenomenon was first called “Hammer’s phantom shadow,” but when Edison patented the bulb in 1883 it became known as the “Edison effect.” Scientists later determined that this effect was explained by the thermionic emission of electrons from the hot to the cold electrode, and it became the basis of the electron tube and laid the foundation for the electronics industry.Edison had moved his operations from Menlo Park to New York City when work commenced on the Manhattan power system. Increasingly, the Menlo Park property was used only as a summer home. In August 1884 Edison’s wife, Mary, suffering from deteriorating health and subject to periods of mental derangement, died there of “congestion of the brain,” apparently a tumour or hemorrhage. Her death and the move from Menlo Park roughly mark the halfway point of Edison’s life.

The Edison laboratoryA widower with three young children, Edison, on February 24, 1886, married 20-year-old Mina Miller, the daughter of a prosperous Ohio manufacturer. He purchased a hilltop estate in West Orange, New Jersey, for his new bride and constructed nearby a grand, new laboratory, which he intended to be the world’s first true research facility. There, he produced the commercial phonograph, founded the motion-picture industry, and developed the alkaline storage battery. Nevertheless, Edison was past the peak of his productive period. A poor manager and organizer, he worked best in intimate, relatively unstructured surroundings with a handful of close associates and assistants; the West Orange laboratory was too sprawling and diversified for his talents. Furthermore, as a significant portion of the inventor’s time was taken up by his new role of industrialist, which came with the commercialization of incandescent lighting and the phonograph, electrical developments were passing into the domain of university-trained mathematicians and scientists. Above all, for more than a decade Edison’s energy was focused on a magnetic ore-mining venture that proved the unquestioned disaster of his career.

Thomas Edison

Thomas Edison (right) in his laboratory in West Orange, N.J., with his assistant.

Thomas Edison