|

Site Categories |

|

Featured Items |

Poodle, Spaghetti Trim, Ucagco

|

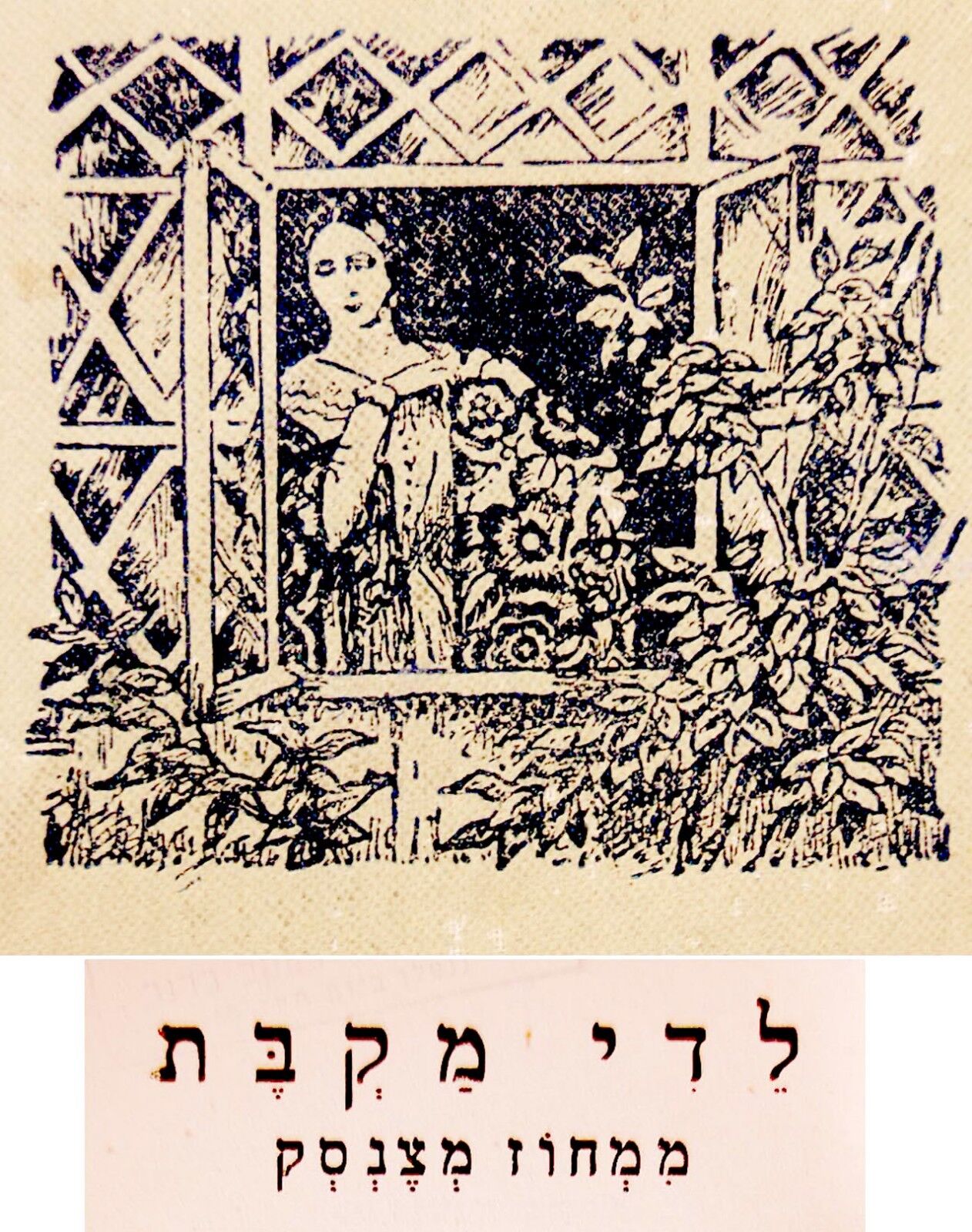

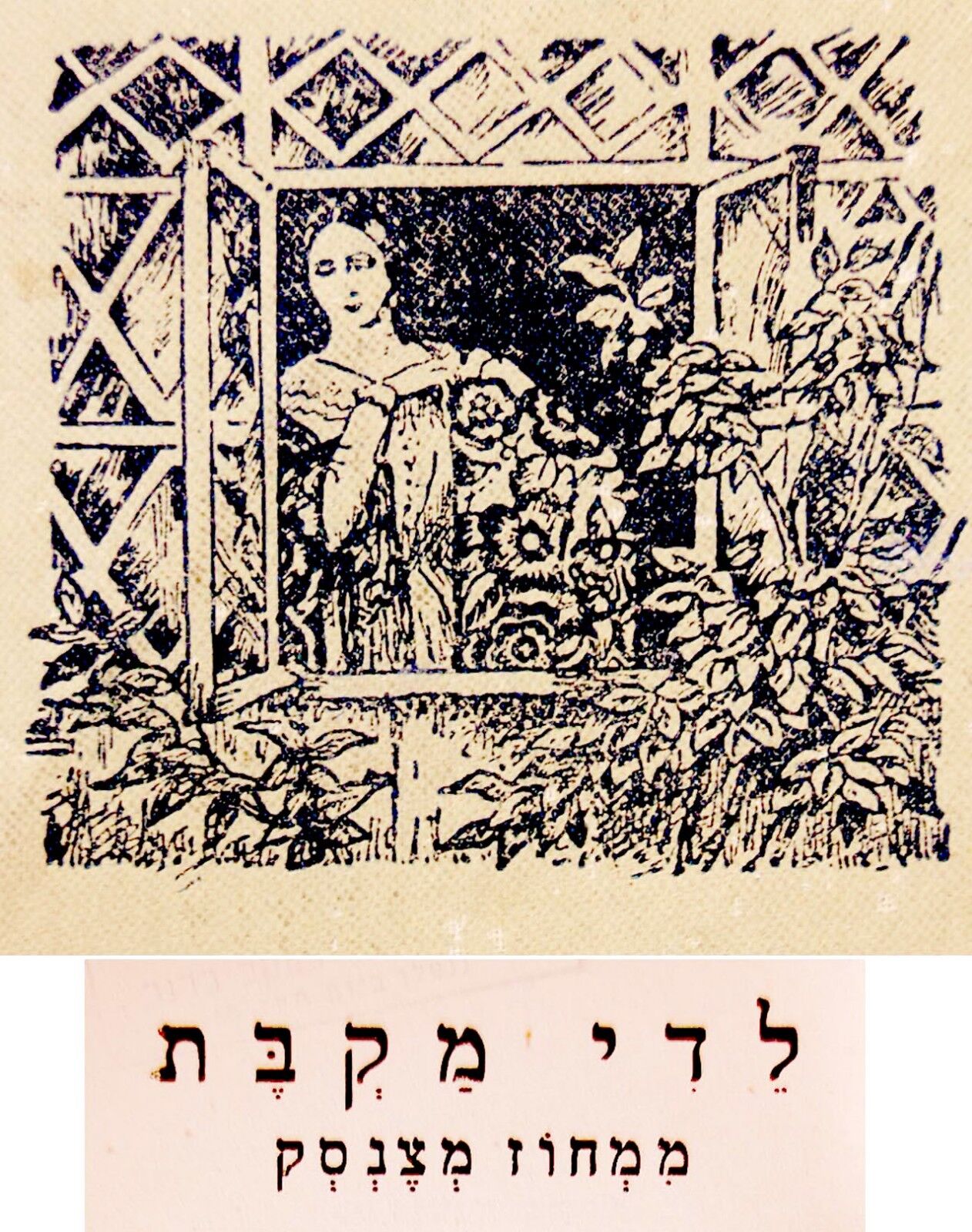

1943 Palestine HEBREW RUSSIAN Book LADY MACBETH Of METSENSK Jewish KUSTODIEV For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

1943 Palestine HEBREW RUSSIAN Book LADY MACBETH Of METSENSK Jewish KUSTODIEV:

$75.00

DESCRIPTION : Here for sale is theFIRSTIsrael EDITION of the richly illustrated RUSSIAN BOOK - \" LADY MACBETH OF THE METSENSK DISTRICT\" by NIKOLAI LESKOV ( Nikolai Semyonovich Leskov Russian: Никола́й Семёнович Леско́в; ) with numerous excellent illustrations by BORIS KUSTODIEV ( Boris Mikhaylovich Kustodiev (Russian: Бори́сМиха́йлович Кусто́диев ) . This 1865 RUSSIAN NOVEL was published in ERETZ ISRAEL - PALESTINE over 70 years ago ( FIRST EDITION - Dated 1943 ) and was translatedto Hebrew by the legendary Russian-Israeli ISRAEL ZEMORAH . This impressive RARE andSOUGHT AFTER edition containsnumerous ILLUSTRATIONS by KUSTODIEV . Original illustrated cloth HC. 4 x 7.5\" . 96 PP . Very good condition. Clean. Loose binding. ( Pls look atscan for accurate AS IS images ) Book willbe sent inside a protective packaging . PAYMENTS : Payment method accepted : Paypal .SHIPPMENT : SHIPP worldwide viaregistered airmail is $ 25 . Book will be sent inside a protective packaging . Will be sentaround 5-10 days after payment . Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District (Russian: Леди Макбет Мценского уезда) is an 1865 novel by Nikolai Leskov. It was originally published in Fyodor Dostoyevsky\'s magazine Epoch. Among its themes are the subordinate role expected from women in 19th-century European society, adultery, provincial life (thus drawing comparison with Flaubert\'s Madame Bovary) and the planning of murder by a woman, hence the title inspired by the Shakespearean character Lady Macbeth from his play Macbeth. The title also echoes the title of Turgenev\'s story Hamlet of the Shchigrovsky District (1859). Leskov\'s story inspired an opera of the same name by Dmitri Shostakovich, and the 1962 Polish film by Andrzej Wajda, Sibirska Ledi Magbet (Siberian Lady Macbeth). Production of an English language feature film adaptation funded by Creative England was announced at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival. Plot summary Chapter 1 The Ismailov family is introduced: Boris, the father of Zinovy, the husband of Katerina for the past five years. Boris and Zinovy are merchants, ruling an estate with many peasant-slaves. Katerina is bored in their empty home, and tired of Boris\' constant orders and scolding of her for not producing any children. She would actually welcome a child, and Zinovy\'s previous wife of twenty years fared no better. Chapter 2 A dam bursts at a mill owned by Boris, and Zinovy leaves town to oversee its repair. Aksinya, the female cook, and Sergei, a newly arrived farmhand, are introduced. Katerina flirts somewhat innocently with Sergei. Aksinya tells Katerina, who has become bored enough to venture out amongst the peasants, of Sergei\'s reputation as a womanizer. Chapter 3 Sergei comes into Katerina\'s room, and after some dialogue about romance, moves to kiss her roughly. She protests at first, but then gives in; after an implied sexual encounter, she tells Sergei to leave because Boris will be coming by to lock her door. He stays, saying he can use the window instead. Chapter 4 After a week of the continued affair, Boris catches Sergei and accused him of adultery. Sergei won\'t admit or deny it, so Boris whips him until his own arm hurts from the exertion, and locks Sergei in a cellar. Katerina seems to come alive from her boredom, but Boris threatens to beat her as well when she asks for Sergei\'s release. Chapter 5 Katerina poisons Boris, and he\'s buried without his son and without suspicion. She then takes charge of the estate and begins to order people around, openly being around Sergei every day. Chapter 6 Katerina has a strange dream about a cat. Some dialogue occurs with Sergei, which by its end reveals his worry over Zinovy\'s return and desire to marry her. Chapter 7 Katerina again dreams of the cat, which this time has Boris\' head rather than a cat\'s. Zinovy returns and takes some time getting around to confront Katerina with what he\'s heard about her affair. Finally she calls Sergei in, kisses him in front of her husband, some violence occurs, and the two of them are strangling Zinovy. Chapter 8 Zinovy dies, and Sergei buries him deep in the walls of the cellar where he himself had been kept. Chapter 9 Some convenient circumstances regarding Zinovy\'s return shroud his disappearance in mystery, and while there\'s an inquiry, nothing is found and no trouble comes to Sergei or Katerina. The latter becomes pregnant. Everything seems to be working out for them, until Boris\' young nephew Fyodor shows up with his mother, preventing Katerina from inheriting the estate. She has no problem with this and actually makes an effort to be a good aunt, but Sergei complains repeatedly for a time about their misfortune. Chapter 10 Fyodor falls ill, and Katerina, while tending to him, has a change of heart because of Sergei\'s earlier complaints. Chapter 11 Katerina and Sergei suffocate the boy, but a crowd returning from church storms the house, one of its members having spied the act through the shutters of Fyodor\'s room. Sergei, hearing the windows clattering from the crowd\'s fists, thinks the ghosts of his murder victims have come back to haunt him, and breaks down. Chapter 12 Sergei admits to the crime publicly and, in repentance, also tells of where Zinovy is buried and admits to that crime as well. Katerina indifferently admits that she helped with the murders, saying it was all for Sergei. The two are sent to exile in Siberia. During their journey there, Katerina gives birth in a prison hospital, and wants nothing to do with their child. Chapter 13 The child is sent to be raised by Fyodor\'s mother and becomes heir to the Ismailov estate. Katerina continues to be obsessed with Sergei, who increasingly wants nothing to do with her. Fiona and \"little Sonya,\" two members of the prison convoy with Katerina and Sergei, are introduced, the former being known for being sexually prolific, the latter the opposite. Chapter 14 Sergei is caught by Katerina while being intimate with Fiona. Katerina is mortified, but seeing Fiona\'s indifference to the whole situation, reaches something approaching cordiality with Fiona by writing her off. Sergei then pursues little Sonya, who won\'t sleep with him unless he gives her a pair of stockings. Sergei then complains to Katerina about his ankle-cuffs. She, being happy that he\'s talking to her again, readily gives him her last pair of new stockings to ease his pain, which he then gives to Sonya for sexual favours. Chapter 15 Katerina sees Sonya wearing her stockings, and spits in Sergei\'s eyes, and shoves him. He promises revenge, and later breaks into her cell with another man, giving her fifty lashes with a rope, while Katerina\'s cell-mate Sonya giggles in the background. Katerina, broken, lets Fiona console her, and realizes that she is no better than Fiona, which is her last straw: after that she is emotionless. On the road in the prison convoy, Sergei and Sonya together mock Katerina. Sonya offers her stockings to her for sale. Sergei reminisces about both their courtship and their murders in the same airy manner. Fiona and an old man in the convoy, Gordyushka, defend Katerina, but to no avail. The convoy arrives at a river and boards a ferry, and Katerina, repeating some phrases similar to Sergei\'s feigned nostalgia for their life at the estate, tackles Sonya overboard after seeing the faces of Boris, Zinovy, and Fyodor in the water. The two women appear briefly at the surface, still alive, but Katerina grabs Sonya, and they both drown.Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk by Nikolai Leskov, Nikolai Leskov, Robert Chandler (Goodreads Author) (Translator), Gilbert Adair (Foreword by) 3.98 · Rating Details · 1,566 Ratings · 40 Reviews In this powerful and brutal short story, Leskov demonstrates the enduring truth of the Shakespearean archetype joltingly displaced to the heartland of Russia. Chastened and stifled by her marriage of convenience to a man twice her age, the young Katerina Lvovna goes yawning about the house, missing the barefoot freedom of her childhood, until she meets the feckless steward Sergei Filipych. Sergei proceeds to seduce Katerina, as he has done half the women in the town, not realizing that her passion, once freed, will attach to him so fiercely that Katerina will do anything to keep hold of him. Journalist and prose writer Nikolai Leskov is known for his powerful characterizations and the quintessentially Russian atmosphere of his stories. Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk is not just a powerful critique of the Soviets but of Russia today Russia’s desperate housewife Mark Wigglesworth Sunday 20 September 2015 1 comment85 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk Annie Lydford The notion that opera is a glamorous and frivolous entertainment for the social and cultural elite may be a convenient stereotype, but for those who have experienced it nothing could be further from the truth. The vast majority of operas address subjects that are both real and relevant. Love and death, religion and sex, power, friendship and betrayal are fundamental concerns of the human condition and to hear them expressed through the elemental voices of music and drama is to make a connection with their significance that is profound and enjoyable.Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk is a perfect example. The composer intended it to be the first of four operas focusing on the plight of women throughout different eras of Russian history. “I want to write a Soviet Ring of the Nibelungs,” he said. “It will be an operatic tetralogy about women.” The initial success of Lady Macbeth was astounding, receiving more than 200 performances in its first couple of years alone. At one point Moscow had three separate productions running simultaneously. To the Soviet authorities however, feminism was a threatening concept. A few days after Stalin walked out of a performance of the opera, Pravda described the work as a “cacophonous and pornographic insult to the Soviet people”. The message of the article was unambiguous. Unless the composer of this “degenerate opera” changed his ways, things could end very badly. The piece was banned and Shostakovich became “an enemy of the people”. He never wrote another opera. There is something puzzling about the extreme and drastic nature of the official response to the piece. Taken at face value, the story of Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk can be seen as a perfectly valid argument for the need to overthrow Russia’s Tsarist autocracy. And the music offers no particular challenge to those who at the time believed that operas should be tuneful and popular. It has to have been the result of a far more sensitive button being pressed.Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk takes place in a narrow-minded and provincial town of stifling mediocrity, where the male characters are impotent idiots, violent thugs, or both, and the women are almost all victims of physical and emotional abuse. In fact the significant changes that Shostakovich made to Nikolai Leskov’s short story on which the opera is based, all increase our understanding of Katerina, the triple-murderess in question, and encourage us to feel sympathy for her as a victim of her circumstances and conditions. “A turn of events is possible in which murder is not a crime,” Shostakovich wrote. He pours all his compassion into music of such sublime beauty and tenderness that the listener has little choice but to side with Katerina’s passion, sensitivity, love, sexuality, vulnerability, dignity and strength. The composer agreed that the piece might more accurately be called “Desdemona” or “Juliet of Mtsensk”.Shostakovich wrote that the opera is “the truthful and tragic portrayal of the destiny of a talented, smart, and outstanding woman, dying in the nightmarish conditions of pre-revolutionary Russia”. Dedicated to his new bride, it is, in part, unquestionably about the power of love, especially new love, to drive us to irrational and extreme acts. But the extra justification he gives Katerina’s crimes show that the work is also about the oppression of women generally. “I wanted to unmask reality,” Shostakovich said, “and to arouse a feeling of hatred for the tyrannical and humiliating atmosphere in a Russian merchant’s household.”Set in the 19th century, written in the 20th, and performed in the 21st, Lady Macbeth allows us at English National Opera to argue the continued relevance of opera louder than ever. Around 14,000 Russian women die each year as a result of domestic abuse, a crime that is still not classified as such in Russia. “If he beats you, he loves you” is even a Russian proverb. In her book Sex, Politics and Putin, Valerie Sperling argues that the contemporary sexualisation of political figures, in particular the machismo image of President Putin, reinforces gender norms in Russia that are misogynistic, and used as platforms for power. In passing sentence recently on the members of the Pussy Riot punk-rock group, the judge claimed it was their feminism that lay at the heart of their anti-religious beliefs, and therefore their crime. The implication is that women are dangerous unless they are at home – a home that in Lady Macbeth, Katerina finds intolerably boring and suppressive. No wonder Stalin didn’t like it.Political revolutions can be quick, but it seems social evolution is a longer process. Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk is a cry for help – a plea for personal freedom, and for the rights of the individual to be respected. It is a cry that in some places continues to be unheeded. History shows that history is easily ignored. Our ability to correct the errors of our past is more limited than we care to admit. Shostakovich’s music is at its most beautiful when it expresses the empathy he feels towards the vulnerable. It is at its most important wherever and whenever these victims still exist. Boris Mikhaylovich Kustodiev (Russian: Бори́с Миха́йлович Кусто́диев) (March 7, 1878 – May 28, 1927) was a Russian painter and stage designer.[1][2] Contents 1 Early life2 Art studies3 Career 3.1 Stage design4 Selected works5 See also6 References7 External links Early life Boris Kustodiev was born in Astrakhan into the family of a professor of philosophy, history of literature, and logic at the local theological seminary.[1] His father died young, and all financial and material burdens fell on his mother\'s shoulders.[2] The Kustodiev family rented a small wing in a rich merchant\'s house. It was there that the boy\'s first impressions were formed of the way of life of the provincial merchant class. The artist later wrote, \"The whole tenor of the rich and plentiful merchant way of life was there right under my nose... It was like something out of an Ostrovsky play.\"[2] The artist retained these childhood observations for years, recreating them later in oils and water-colours.[2] Art studies Winter-festivities 1919 Between 1893 and 1896, Boris studied in theological seminary and took private art lessons in Astrakhan from Pavel Vlasov, a pupil of Vasily Perov.[3] Subsequently, from 1896 to 1903, he attended Ilya Repin’s studio at the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg.[1] Concurrently, he took classes in sculpture under Dmitry Stelletsky and in etching under Vasiliy Mate.[1] He first exhibited in 1896.[1] \"I have great hopes for Kustodiev,\" wrote Repin. \"He is a talented artist and a thoughtful and serious man with a deep love of art; he is making a careful study of nature...\"[4] When Repin was commissioned to paint a large-scale canvas to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the State Council, he invited Kustodiev to be his assistant. The painting was extremely complex and involved a great deal of hard work. Together with his teacher, the young artist made portrait studies for the painting, and then executed the right-hand side of the final work.[5] Also at this time, Kustodiev made a series of portraits of contemporaries whom he felt to be his spiritual comrades. These included the artist Ivan Bilibin (1901, Russian Museum), Moldovtsev (1901, Krasnodar Regional Art Museum), and the engraver Mate (1902, Russian Museum). Working on these portraits considerably helped the artist, forcing him to make a close study of his model and to penetrate the complex world of the human soul.[2] In 1903, he married Julia Proshinskaya (1880–1942).[6][7] He visited France and Spain on a grant from the Imperial Academy of Arts in 1904. Also in 1904, he attended the private studio of René Ménard in Paris. After that he traveled to Spain, then, in 1907, to Italy, and in 1909 he visited Austria and Germany, and again France and Italy. During these years he painted many portraits and genre pieces. However, no matter where Kustodiev happened to be – in sunny Seville or in the park at Versailles – he felt the irresistible pull of his motherland. After five months in France he returned to Russia,[2] writing with evident joy to his friend Mate that he was back once more \"in our blessed Russian land\".[2] Career Pancake Tuesday; Butter Week or Crepe week, (1916) The Russian Revolution of 1905, which shook the foundations of society, evoked a vivid response in the artist\'s soul. He contributed to the satirical journals Zhupel (Bugbear) and Adskaya Pochta (Hell’s Mail). At that time, he first met the artists of Mir Iskusstva (World of Art), a group of innovative Russian artists. He joined their association in 1910 and subsequently took part in all their exhibitions.[2] In 1905, Kustodiev first turned to book illustrating, a genre in which he worked throughout his entire life. He illustrated many works of classical Russian literature, including Nikolai Gogol\'s Dead Souls, The Carriage, and The Overcoat; Mikhail Lermontov\'s The Lay of Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich, His Young Oprichnik and the Stouthearted Merchant Kalashnikov; and Leo Tolstoy\'s How the Devil Stole the Peasants Hunk of Bread and The Candle.[2] Blue House (1920). In 1909, he was elected into Imperial Academy of Arts.[2] He continued to work intensively, but a grave illness—tuberculosis of the spine—required urgent attention.[6] On the advice of his doctors he went to Switzerland, where he spent a year undergoing treatment in a private clinic.[6] He pined for his distant homeland, and Russian themes continued to provide the basic material for the works he painted during that year. In 1918, he painted The Merchant\'s Wife, which became the most famous of his paintings.[6] In 1916, he became paraplegic.[1] \"Now my whole world is my room\", he wrote.[4] His ability to remain joyful and lively despite his paralysis amazed others. His colourful paintings and joyful genre pieces do not reveal his physical suffering, and on the contrary give the impression of a carefree and cheerful life. His Pancake Tuesday/Maslenitsa (1916) and Fontanka (1916) are all painted from his memories. He meticulously restores his own childhood in the busy city on the Volga banks.[8] In the first years after the Russian Revolution of 1917 the artist worked with great inspiration in various fields. Contemporary themes became the basis for his work, being embodied in drawings for calendars and book covers, and in illustrations and sketches of street decorations, as well as some portraits (Portrait of Countess Grabowska). Kustodiev Trinity day, 1920 His covers for the journals The Red Cornfield and Red Panorama attracted attention because of their vividness and the sharpness of their subject matter. Kustodiev also worked in lithography, illustrating works by Nekrasov. His illustrations for Leskov\'s stories The Darner and Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District were landmarks in the history of Russian book designing, so well did they correspond to the literary images.[2] Stage design The artist was also interested in designing stage scenery. He first started work in the theatre in 1911, when he designed the sets for Alexander Ostrovsky\'s An Ardent Heart. Such was his success that further orders came pouring in. In 1913, he designed the sets and costumes for The Death of Pazukhin at the Moscow Art Theatre. His talent in this sphere was especially apparent in his work for Ostrovsky\'s plays; It\'s a Family Affair, A Stroke of Luck, Wolves and Sheep, and The Storm. The milieu of Ostrovsky\'s plays—provincial life and the world of the merchant class—was close to Kustodiev\'s own genre paintings, and he worked easily and quickly on the stage sets.[2] In 1923, Kustodiev joined the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia. He continued to paint, make engravings, illustrate books, and design for the theater up until his death of tuberculosis on May 28, 1927, in Leningrad.[1] Boris Kustodiyev at Artprice. To look at sale records, find Kustodiev\'s works in upcoming sales, check price levels and indexes for his works, read his biography and view his signature, access the Artprice database.Boris Mikhailovich Kustodiev was born in Astrakhan on March 7, 1878 into the family of a professor of philosophy, history of literature, and logic at the local theological seminary. Between 1893 and 1896, Boris took private art lessons in Astrakhan from Pavel Vlasov, a pupil of Vasily Perov. Subsequently, from 1896 to 1903, he attended Ilya Repin’s studio at the Academy of Arts in St. Peterburg. Concurrently he took classes in sculpture under Dmitry Stelletsky and in etching under Vasily Mathé.He first exhibited in 1896. In 1904, he attended the private studio of René Ménard in Paris. In 1904, he traveled to Spain, in 1907 to Italy, and in 1909 visited Austria, France, and Germany, and again Italy. During these years he painted many portraits and genre pieces. In 1905-06, he contributed to the satirical journals Zhupel (Bugbear) and Adskaya Pochta (Hell’s Mail). At that time, he first met the World of Art (Russian: Mir Iskusstva) artists, a group of innovative Russian artists. He joined their association in 1910 and subsequently took part in all their exhibitions. Earlier, in 1909, he was made an Academician of Painting. In 1909, Kustodiev developed the initial symptoms of the grave illness that in 1916 paralyzed the lower part of his body, thus confining him to his studio where he continued to paint, relying on memories from his boyhood and youth and on his imagination. His ability to remain joyful and lively despite his paralysis is amazing. His colorful paintings and joyful genre pieces do not reveal his physical suffering, and on the contrary give the impression of a carefree and cheerful life. His Pancake Tuesday/Maslenitsa. (1916), Fontanka. (1916) are all painted from his memories. He meticulously restores his own childhood in the busy city on the Volga banks. In 1923, Kustodiev joined the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia. He continued to paint, make engravings, illustrate books and design for the theater up until his death on May 28, 1927, in Leningrad. Bibliography:Kustodiev. His Time, Life and Work. By V.Lebedeva. Moscow, 1984.Boris Kustodiev. By A. Turkov. 1986, MoscowBoris Kustodiev. By V. Dokuchaeva. Moscow, 1991.Russian Painters. Encyclopedic Dictionary. St. Petersburg. 1998.Boris Kustodiev--paintings, graphic works, book illustrations, theatrical designs by Boris Mikhailovich Kustodiev. Aurora Art Publishers, 1983.The Art and Architecture of Russia (Pelican History Art) by George Heard Hamilton. Yale Univ Pr, 1992.A Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Artists 1420-1970 by John Milner. Antique Collectors\' Club, 1993. Boris Mikhailovich Kustodiev (1878-1927)Boris Kustodiev has a place of honour among those artists of the early twentieth century. A talented genre-painter, master of psychological portraiture, book illustrator and stage-set artist, Kustodiev produced masterpieces in almost all the imitative arts. But his talent is most apparent in his poetic paintings on themes from the life of the people, in which he conveyed the inexhaustible strength and beauty of the Russian soul. He wrote, \'I do not know if I have been successful in expressing what I wanted to in my works: love of life, happiness and cheerfulness, love of things Russian—this was the only \"subject\" of my paintings ...\' The artist\'s life and work are inseparably linked with the Volga and the wide open countryside of the area, where Kustodiev spent his childhood and youth.His deep love for this area never left him all his life. Boris Kustodiev was bom in Astrakhan. His father, a schoolteacher, died young, and all financial and material burdens lay on his mother\'s shoulders. The Kustodiev family rented a small wing in a rich merchant\'s house. It was here that the boy\'s first impressions were formed of the way of life of the provincial merchant class. The artist later wrote, \'The whole tenor of the rich and plentiful merchant way of life was there right under my nose ... It was like something out of an Ostrovsky play.\' The artist retained these childhood observations for years, recrceating them later in oils and water-colours. The boy\'s interest in drawing manifested itself at an early age. An exhibition of Peredvizhniki which he visited in 1887, and where he saw for the first time paintings by \'real\' artists, made a tremendous impression on him, and he firmly resolved to become one himself. Despite financial difficulties, his mother sent him to have lessons with a local artist and teacher A. Vlasov, of whom Kustodiev always retained warm memories. Graduating from a theologicalseminary in 1896, Kustodiev went to St. Petersburg and entered the Academy of Arts. He studied in Repin\'s studio, where he did a lot of work from nature, trying to perfect his skill in conveying the colourful diversity of the world. \'I have great hopes for Kustodiev, \'wrote Repin. \'He is a talented artist and a thoughtful and serious man with a deep love of art; he is making a careful study of nature ...\' When Repin was commissioned to paint a large-scale canvas to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the State Council, he invited Kustodiev to be his assistant. The work was extremely complex and involved a great deal of hard work. Together with his teacher, the young artist made portrait studies tor the painting, and then executed the right-hand side of the final work. At this time too, Kustodiev made a series of portraits of contemporaries whom he felt to be his spiritual comrades. These included the artist *Bilibin* (1901, RM), *Moldovtsev* (1901, Krasnodar Renional Art Museum) and the engraver *Mate* (1902, RM). Working on these portraits considerably helped the artist, forcing him to make a close study of his model and to penetrate the complex world of the human soul. In the summer of 1903 Kustodiev undertook a long trip down the Volga from Rybinsk to Astrakhan, in search of material for a program painting set by the Academy. The colourful scenes at bazaars along the Volga, the quiet provincial sidestreets and the noisy quays made a lasting impression on the artist, and he drew on these impressions for his diploma work, *Village Bazaar* (not preserved). Upon graduating, he obtained the right to travel abroad tofurther his education, and left in 1903 for France and Spain. Kustodiev studied the treasures of Western European art with great enthusiasm and interest, visiting the museums of Paris and Madrid. During his trip he painted one of his most lyrical paintings, *Morning* (1904, RM), which is suffused with light and air, and may be seen as a hymn to motherhood, to simple human joys. However, no matter where Kustodiev happened to be—in sunny Seville or in the park at Versailles—he felt the irresistible pull of hismotherland. After five months he returned to Russia. Joyfully he wrote to his friend Mate that he was back once more \'in our blessed Russian land\'. The revolutionary events of 1905, which shook the foundations of society, evoked a vivid response in the artist\'s soul. He did work for the satirical journals Bugbear and Infernal Post, drawing vicious caricatures of prominent tsarist officials such as Ignatiev, Pobedonostsev and Dubasov. He also made drawings directly related to the revolutionary events (The Agitator and Meeting) which for the first time showed a revolutionary leader together with a mass of working people. Tn paintings such as *Meeting at Putilovsky Factory*, *Strike*, *Demonstration* and *The May-Day Demonstration at Putilovsky Factory* (1906, Museum of the Revolution, Moscow), he depicted workers rising in the struggle against autocracy. Kustodiev was deeply distressed by the defeat of the revolution. His drawing *Moscow. Entry* (1905, TG) is an allegory on the cruel suppression of the December uprising. Houses are being destroyed, people are dying. Soldiers fire on the demonstrators, and Death reigns over all. Scenes of bloody violence against demonstrating workers are also portrayed in the drawing *February; After she Dispersal of a Demonstration* (1906). In 1905 Kustodiev first turned to book illustrating, a genre in which he worked throughout his entire life. He illustrated many works of classical Russian literature, including Gogol\'s *Dead Soul, The Carriage and The Overcoat*, Lermontov\'s *The Lay of Tsar Ivan Vassilyevich, His Young Oprichnik and the Stouthearted Merchant Kalashnikov* and Lev Tolstoy\'s *How the Devil Stole the Peasants Hunk of Bread* and *The Candle*. Kustodiev also continued to work in portraiture. His Portrait of a *Priest and a Deacon* (1907, Gorky Art Museum) and *The Nun* (1908, RM) are complex and vivid in their characterization. His sculptured portraits are also varied in form and characterization. That of *I. Yershov* (1908, Kirov Opera and Ballet Theatre) shows us the noble, imposing figure of the singer, while in the sculpture of Mstislav Dobuzhinsky we see the artists troubled, searching nature. It was at this time that the circle of images and themes formed which would serve as the basis of the bulk of Kustodiev\'s work. He was very fond of folk art—painted toys from Vyatka and popular prints—and studied folk tales, legends and superstitions. He believed that in the minds of ordinary people art was always connected with celebration and rejoicing. In 1906 he painted *The Fair* (TG), in which a colourful crowd is seen milling about outside the merchants\' stalls. Although the scene portrayed is commonplace and seemingly ahlf-hazard, much thought and care was put into the composition of the piece. The bold combinations of bright colours lend it a decorativeness not unlike that of popular prints of the time. Kustodiev was also attracted by the theme of gay village festivals and merrymaking, with their brightness, spontaneity and coarse folk humour: cf. *Village Festival* (1907, TG), *Merrymaking on the Volga* (1909, Kostroma Museum of Local History). These paintings were very popular at exhibitions both in Russia and abroad. In 1909 Kustodiev was awarded the title of Academician of Art. He continued to work intensively, but a grave illness—tuberculosis of the spine—required urgent attention. On the advice of his doctors he went to Switzerland, where he spent a year undergoing treatment in a private clinic. He pined for his distant homeland, and Russian themes continued to provide the basic material for the works he painted during that year. In 1912 he painted *Merchant Women* (Kiev Museum of Russian Art), in which fact and fantasy, genuine beauty and imitation, are intermingled. Well-dressed, stately, healthy looking merchant women are having an unhurried conversation in the market-place. Their silk dresses shimmer with all the colours of the rainbow, and their painted shawls are ablaze with rich colours. Roundabout, the brightly-coloured signs above the stalls seem to echo all of this. In the distance a red churchwith golden cupolas and a snow-white bell-tower are clearly visible. The artist\'s perception of the world is festive, cheerful and unclouded. Although his illness became progressively worse, Kustodiev\'s work remained radiant and optimistic. ...The Moscow cab drivers seated round their glasses of tea in the painting *Moscow Inn* (1916, TG) are acting out the tea-drinking ritual with great solemnity and seriousness. A grammophon is straining, a cat is purrying and a waiter is dozing in a chair. The picture is full of witty pointed details. The inhabitants and life of provincial towns were the main subjects of Kustodiev\'s genre-painting at this time. His talent is especially apparent in three paintings in which he sought to create generalized, collective images of feminine beauty: *The Merchant\'s Wife* (1915, RM), *Girl on the Volga* (1915, Japan) and *The Beauty* (1915, TG). In the *Merchant\'s Wife* we have a captivating picture of a dignified Russian beauty, full-busted and glowing with health. The radiant yellows, pinks and blues of the background landscape set off the reddish-brown tone of her dress and her flowery shawl, and everything mingles together in her bright colourful bouquet. Another of Kustodiev\'s characters, in *The Beauty*, cannot fail to attract the viewer. There is great charm and grace in the portrayal of the plump fair-haired woman seated on a chest. Her funny, awkward position reflects her naively and chaste purity, and her face is a picture of softness and kindness. Maxim Gorky was very fond of this painting, and the artist presented him with one of the variants he made of it. The genre works which Kustodiev painted at this time describe the world of small provincial towns: cf. *The Small Town* (1915. private collection, Moscow) and *Easter Congratulations* (1916, Kustodiev An Gallery, Astrakhan). This series was completed by one of his finest paintings,*Shrovetide* (1916, RM), which continued the theme of popular festivals. Despite his serious illness, Kustodiev continued to work. He underwent a complex operation, but to no avail. Now his legs were completely paralyzed. He wrote, \'Now my whole world is my room.\' In the first years after the Revolution the artist worked with great inspiration in various fields. Contemporary themes became the basis for his work, being embodied in drawings for calendars and book covers, and in illustrations and sketches of street decorations. His covers for the journals The Red Cornfield and Red Panorama attracted attention because of their vividness and the sharpness of their subject matter. Kustodiev also worked in lithography, illustrating works by Nikolai Nekrasov. His illustrations for Leskov\'s stories The Darner and Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District were landmarks in the history of Russian book designing, so well did they correspond to the literary images. The artist was also interested in designing stage scenery. He first started work in the theatre in 1911, when he designed the sets for Ostrovskv\'s *An Ardent Heart*. Such was his success that further orders came pouring in; in 1913 he designed the sets and costumes for *The Death of Pazukhin* at the Moscow Art Theatre. His talent in this sphere was especially apparent in his work for Ostrovsky\'s plays; *It\'s a Family Affair*, *A Stroke of Luck*, *Wolves and Sheep* and *The Storm*. The milieu of Ostrovsky\'s plays—provincial life and the world of the merchant class —was close to Kustodiev\'s own genre paintings, and he worked easily and quickly on the stage sets. Kustodiev\'s sudden death on 26 May 1927 was a great loss to Soviet art, but his bright and optimistic works live on: a source of great pleasure for millions. 3356

|

|

Related Items:

Jewish Judaica 1943 Palestine Israel Pardes Hanna Pioneers Photo $38.00

1943 Palestine MOI VER Vorobeichic PHOTO BOOK Jewish WILNA Bauhaus HEBREW Israel $125.00

PALESTINE JUDAICA ANDERS RECHOVOT POLISH ARMY WWII PHOTO 1943 $139.99

|

|

|

Shopping Cart  |

|

Recently Viewed |

|

Latest Items |

|

Facebook |

Secure Websites

|